Jesse Ed Davis: Washita Love Child

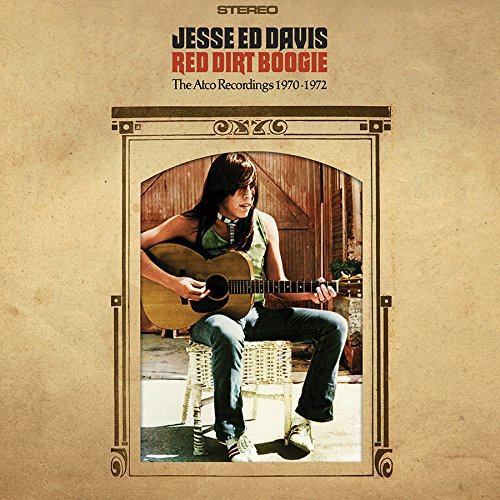

Native American guitar prodigy JESSE ED DAVIS was sidesman for legends such as John Lennon, Gene Clark, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, and released a trio of solo albums in the early ‘70s. THOMAS PATTERSON hears personal memories of a man who died young but burned brightly from Mike Johnson, producer of new compilation Red Dirt Boogie: The Atco Recordings 1970-1972

I was a big fan of Jesse, because I’m a Beatles’ freak. I had a lot of the bootlegs, going back into the early ‘70s. I had the Walls and Bridges session that he was very prominent on.

Being in LA, I read in the LA Weekly that Yoko Ono was doing an art show. This was in 1985, and I thought, “I’m going to crash it and see if I can get in.” I was waiting in line at the gallery, and I noticed Jesse was in line a few people back. I invited him up to where I was standing, two from the door. I said, “I’m a big fan, I know your work.” I ran his discography by him. He was very interesting, he wanted to talk. When the door opened, we went in and mingled, and Jesse saw Yoko, and took me with him, and introduced me. “Mike Johnson, this is Yoko Ono.” And I thought, “Holy cow, I’ve arrived!”

We spoke for a few minutes then Jesse took Yoko off to the side. I don’t know what they talked about but it looked very serious and then she left. Was he there to ask her for money, was he there to ask for a favour, as he there just out affection? I never knew and I never asked. But while we were in line, we exchanged phone numbers. A few days went by and he actually called me. I was at work, and he asked if I were ever around, could I give him a lift? And I said, “Sure, I can take you wherever you need to go.” And that’s where it started.

I was always really honoured when Jesse would call and ask for a favour like that. It was just really cool having that audience with him, one on one in my car as we’re driving some place. Many times I didn’t ask him why we were going somewhere, it was kind of weird. Of course, this was way back before Uber. But by picking him up and driving him places, I could ask him questions.

He lived on Sawtelle in Palms. Often, I’d be in his apartment and he’d show me things – he had tapes, he had photographs. I was seeing Polarioids and photographs that weren’t in an album but were in a shoebox. And he this old TV tray, and underneath this tray was the box of photos. He’d loan me cassettes, things like Taj Mahal live at The Fillmore. He was a giving sort, it was tit for tat. And sometimes he’d come and hang in my condo in Redondo, and he’d sit on the sofa and play the blues.

One day I showed up at his, and he said “Did I ever show you this?” It was The Rolling Stones Rock And Roll Circus. It was a rough cut, years before it came out andhe said Bill Wyman had given it to him. And I sat and watched it in his apartment. I thought, “What a wonderful in into this world.” And all I had to do was occasionally loan him twenty dollars and drive him someplace.

Sometimes there was a tinge of sadness. One time I drove him to a county fair in Palm Springs where Richie Havens was playing and he told me he was going out to collect on a debt. And one time I drove him to a pawnshop where he was hawking one of his guitars. But there was nothing I could do. I was always glad to give him a lift and hang, but sometimes after it was over, I would drive home and think, “That was kind of weird.”

The one time I got a call: “Mike, can you drive me to the Palomino?” And I said “No, I’m in Redondo and the Palomino’s all the way up in North Hollywood, I’d have to leave work early.” And of course that was the Taj Mahal show at the Palomino with George Harrison and Bob Dylan. So I didn’t take him to the show of the century! I tell you that only because this project I did is cosmic payment for not going to that gig. He introduced me to Yoko, he could have introduced me to Bob and George, and all I had to do was drive!

He wasn’t doing too much (musically) and that was the sad thing. I talked to (DJ) Allen Larman one time and said “Can we arrange to get Jesse on stage somewhere?” but it never happened. He wasn’t working but it was also the time of The Graffiti Band so he was doing stuff with John Trudell. But I don’t know how much involvement Jesse had. Trudell was definitely the mover.

In essence, I think in the three or four years I knew him, he wasn’t working or performing. But he got involved with Graffiti Band, but it never really went forward.

I knew he was using. You could see his health was seriously deteriorating. It was about week after our last drive when a friend called me and said “Did you hear Jesse died?” And it truly wasn’t a surprise. They found him in the laundry room of the apartment. It was an overdose of heroin, he was shooting. And a couple of the last times I saw him, he was using a cane. I think he was 44.

I knew his stuff well, I was a fan of all the musicians on his albums, but I really got into them after he died. And it was like “Crap, now he’s gone, this is all we have.” And there’s a bootleg of a radio broadcast of him in 1974 at the Santa Monica Civic. It runs for about 45 minutes, perfect quality. And I listen to that and I think, “My God, he really could do it.” I don’t know if he was shy, or was too high or just wanted to be in the background…

But he was proud of his records. I know that Jesse would sometimes say in retrospect, “I was rushed, that wasn’t really my sound, they didn’t capture me right.” But I think every musician says that, and when I would ask him about those records, he was very proud of them.

I have a caveat here, and Jesse would say to me with a sigh, “You know, just one day the circus left town.” And I’d think about that for a long time because you can imagine, here he is, hanging with these cats, and he’s got all this work and everybody’s calling him. One of the cassettes he loaned me was his phone message. Harry Nilsson was on there: “Hey Jesse, this is Harry, we’re in town, gimme a call!” And there was one from Lennon: “Hey this is Dr. Winston O’Boogie, calling from outer space.” Just wonderful messages from everybody. There was definitely a time when he was on the A-List and everybody wanted him to come out to play. But I don’t know if it was just his addiction, or what it was that made the circus leave town. That was one of the big pieces I never figured out. But there was that magic decade where everybody wanted him.

So, during this time and to the present, I’d been working in the music industry. I was with Rhino for a long time in the A&R department and I’m now one of the archivists and I’ve been there 13 years, actually in the main vault. So when a tape is needed for a project, I’m one of six people in the whole company who facilitate assets either physically or electronically. So by proximity to his ATCO/Atlantic recordings, I see them all the time, I walk by these tapes on 16-foot shelves. And by the way we organise things, they’re not in one place, they don’t live as one unit, they come to us at various times, so they’re all over the place. So I’d be re-filing things, think of it as being a librarian, some things would go out, things would come in, you’re constantly circulating assets, and I’m walking past these things all the time and I’d see all these multi-tracks. He left behind a LOT of work. Coming from Rhino I had produced or co-produced many projects, I’ve been involved with over 200 CD titles on the production side. So I thought “I’ve got to get Jesse back out on the street, I’ve got to get these back out there.”

Just trying to push this thing through the system took about five years of asking. Because I couldn’t get the support needed. I don’t have the money to do this myself, so I need a label with clout, and money to be able to licence this stuff. It’s matter of shopping and pushing business affairs. But I just kept pushing. I got a lot of “no’s”. A lot of “Nah, we’re not interested.” But I was persistent. I kept on knocking on the same doors and I wore them down. I’d had some successes with Gordon Anderson at Real Gone Music, and a couple of years ago I did this gigantic box set of unissued Bob Wills’ Tiffany Transcriptions I’d discovered, and it turned out super nice so I’d proved my worth with Gordon by doing that package, so I just kept after them on this project. Eventually they said “Do it, here’s the budget. Go for it.” And it came together really quickly.

There were maybe 60 or more multi-tracks. Two inch 16 track reels. There were 24 songs I’d never heard before including ‘Little Wing’, and it’s got Eric Clapton on it, I determined because of the date. But I couldn’t get anybody to finance that because it’s expensive, about $300 per reel to get those run down. Just to even listen to them, it’s about $300. I wasn’t able to preview much unissued stuff although the tapes sit there. It’s one of those Catch 22 situations. There are tapes but nobody has the money to run them down. That’s the frustration – you see all this genius music that just sits there and I can feel no avenue to get it to the public because it’s very expensive still. Nobody’s going to digitise it. It’ll be 30 years before anybody thinks of digitising those.

But there sit all those multi-tracks and I could ascertain the dates all the recordings were made just by pulling the tapes and just writing down, say, “It was recorded at Criterion on this day and these are the performers”. And I could look at the legal contracts and verify the players and on and on. I also used to do research at the Musicians’ Union, so I had access to the AM/FM recording contracts too, so I knew the dates of the recordings. As I said, I loved this guy.

There was one tape that inspired this project. Five years ago, I came across a tape there that was the spark. I reproduced the front of the tape box in the liner notes of the new package. It was two-track analogue tape and it had Jesse’s handwriting on it. And it was a demo tape he’d put together for Jerry Wexler. And written on the tape was “Here’s the demo recording Jerry, let me know what you think.” And this is the first tape I know of that Jesse part together to send to Jerry Wexler at Atlantic to get a recording contract. And that was one I had run down.

And that’s where the two unreleased songs in the package come from. One is a backing track for ‘Rock N Roll Gypsies’ without the overdubs, and the other is ‘Washita Love Child’ which I just love, but there’s an intro that is like a Native American Pow Wow that runs for a couple of minutes. He definitely chopped that off. He didn’t use that, but there it is, there’s his Native American roots right there, so that was really important to me. There were a couple of songs I left off. ‘Oh Susanne’! What were you thinking, Jesse? So I cherry picked the best. But this easily could have been a double or a triple if we had the budget.

But it’s cosmic payback. He made me feel like a million bucks and all I had to do was drive. Or occasionally open the wallet and stop at a 7/11 and buy him a packet of cigarette. And I knew he was a self-destructive person. He loved to just answer my questions. At some point I ran out of things to ask him. But whether I was an easy mark or we were really friends or it was a combination of the two, it really was a pleasure to have him in my life.

Red Dirt Boogie: The Atco Recordings 1970-1972 is out now on Real Gone