In Conversation With The Reverend Billy G – From The Coachmen and Moving Sidewalks to ZZ Top

The cover stars of Shindig! issue #85 are none other than those titans of Texan rock, ZZ Top. In London to celebrate the release of his latest solo album The Big Bad Blues, ZZ Top’s main man BILLY F. GIBBONS met up with our Contributing Editor THOMAS PATTERSON to chew the fat and share memories about the band’s early years. It’s a wild tale, one that’s recounted in full in the new issue (in UK stores November 1st).

A loquacious, erudite and fascinating interviewee, Billy’s a chap who can spin fantastic yarns about blues greats, psychedelic pioneers, famous studios and legendary LPs – so much so, it’s almost a shame we had to edit his thoughts down for the magazine. So, as an added treat, here’s the unedited transcript of Billy and Thomas’s conversation, full of byways and highways, digressions and laughs. Strap yourselves in and get ready to boogie…

Shindig!: Billy, thanks for sitting down with Shindig!, and congratulations on The Big Bad Blues. It’s such a fun album.

Billy Gibbons: Yes, I must say, it had its inauspicious beginnings in that we had booked some studio time and coincidentally the day we opened the door, our dear friend and drummer from days gone by, Greg Morrow, was passing through Texas. He was on tour with somebody and he had a three-day holiday. And I said, “Well come on in, come on in.” Joe Hardy, the engineer along with our other engineer GL ‘G-Mane’ Moon – it’s a long one – anyway, they got things organised and Joe picked up the bass, Mr Greg Morrow started tapping it out, and I said, “Well, you know, let’s warm up with some of the favourites, the usual Jimmy Reed, BB King, whatnot.” The third day, we wrapped up and Greg said, “You know, reluctantly I have to bow out to get back on the road.” Well Joe said, “Shall we listen to what we’ve been doing for three days?” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Oh, I taped over the red light because the recording was on-going.” That is a bonus. We were just ploughing through it. Caution was to the wind. And that’s how the cover tunes were selected to appear on the record. Two Muddy Waters numbers, ‘Rollin’ And Tumblin’’, which goes back to the ’30s, and then two Bo Diddley numbers, ‘Bring It To Jerome’, a tribute to the maraca player Jerome Green and ‘Crackin’ Up’. ‘Crackin’ Up’ has an interesting background. The guitar figure that opens the song in the original Bo Diddley recording from 1957 is inside and out, upside down and backwards. I had talked about this particular track with Keith Richards. And he and I had joined the legions of curious listeners trying to figure out that opening figure. And he gave up. He said “Oh no, it’s only done once, it’s on the record.” It took days to try and figure it out. I came close. And I think if Bo Diddley were sitting here now he’d probably say, “Yeah, OK, close enough, now let’s do another one.” (Laughs) I’d say, “One’s too many and a hundred ain’t enough!”

SD!: You came from a musical family, right? You picked up the guitar aged 13.

BG: Exactly. 13. Xmas day. I turned 13 December 16th and nine days later my dad reached behind the tree and I said, “Wow a guitar, yeah!” And then he pulled out a little table top Fender amp and I said, “Wow an electric guitar!” (laughs).

SD!: But before that, is it true you studied percussion with Tito Puente?

BG: When I was 12, my sister and I, we spent a little over a year down in Mexico City with our next-door neighbours. The dad of that family was some big shot with Standard Oil, which was partners with the Mexican government, they’d nationalised their oil, P-Mex. And they had some problem down in Mexico. So my buddy who lived next door he said, “Oh yeah, we’ve got to go down to Mexico, there’s some problem, my Dad’s going to put that fire out, we’ll be back in a couple of weeks.” Well, a couple of months later he called up and said, “Dude, we’re never getting out of here! Can you come down?” And I said, “Well it’s summer, summer’s next week, we get out of school.” So my folks willingly sent us on our way.

So coming back, I’d just turned 12 and I was banging on everything around the house. And I had a little metal trashcan and a couple of pencils and I was just going after it. But my dad stepped in and he said, “Listen, if you’re going to continue banging on things, let’s learn to do it correctly.” I didn’t really know what he had up his sleeve. Next thing I know I’m on a plane from Texas up to New York City by myself, going into Spanish Harlem, knocking on the door which swings open and there was Tito Puente who I didn’t know. He thrust a couple of timbale sticks and said, “Show me what you want to play.” And I was like, “Oh, I don’t know.” But that was the start of it. And I wound up staying a little over a month. But man, if it had Latin attached to any form of percussion, he had it together. And he had all the correct techniques. And I came to learn who I was in the presence with, the Mambo King! And bongos, conga, timbales, maracas, claves, pescado, you name it. After that first frightful encounter, I really started getting into it. But that came in handy with the previous solo record. Those studio sessions, the two engineers, when I announced we were going to make a Cubanized record – “Gibbons finally lost his mind!” But as the old saying goes, it’s like learning to ride a bicycle. It all came back, handily. And again we had a blast making that one.

SD!: How quickly did you adapt to the guitar?

BG: By that night, I had the Jimmy Reed on the bottom string. Dan-ta-Dan-ta, Dan-ta- Dan-ta. We called it the ‘Danta danta,’ you know.

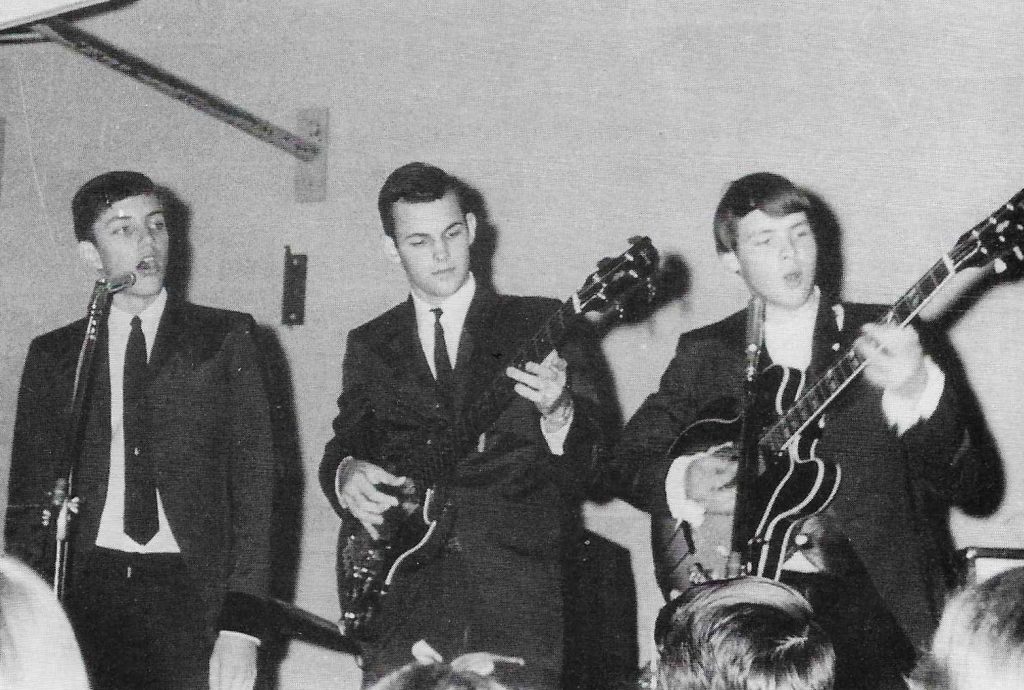

SD!: So you’ve got your guitar, you form a few bands, but the one that really gets things going is The Coachmen.

BG: That was the start. This will take me just a moment, but I’m glad you brought that up. A lot of folks say, “Oh yeah, we know ZZ Top and before that was The Moving Sidewalks.” Before that, this really will take you back…

(Billy pulls out his phone and starts scrolling through the pictures)

It’s patently ridiculous but I opened up the email and someone said, “Do you remember this business card?” And I was like “What?!”

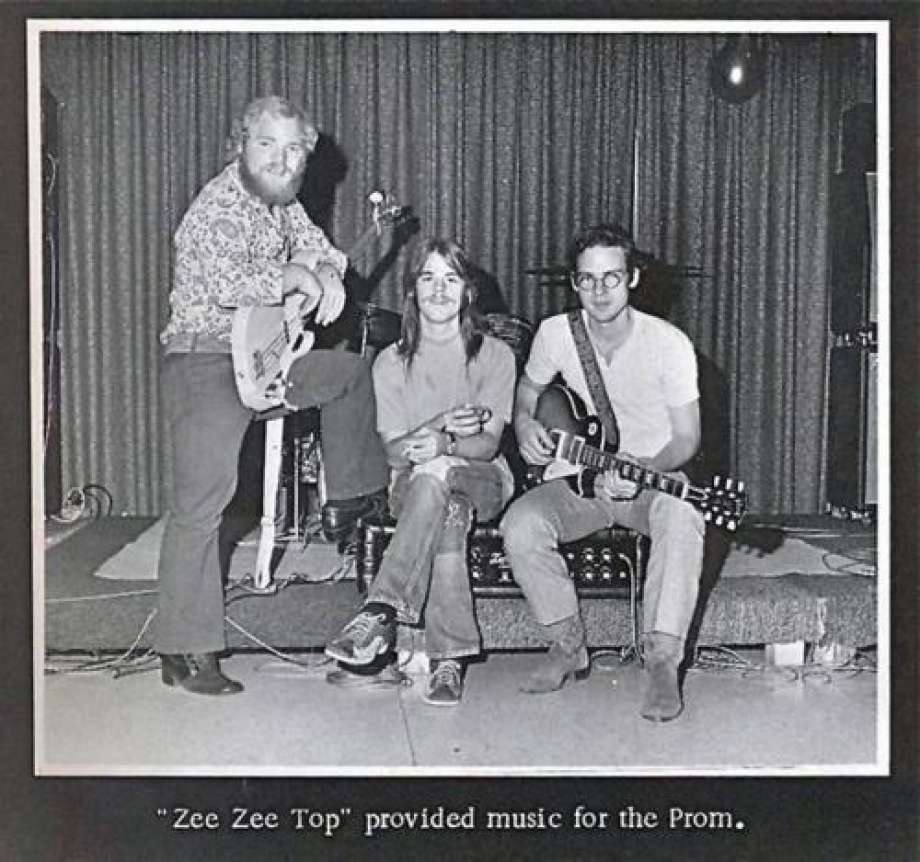

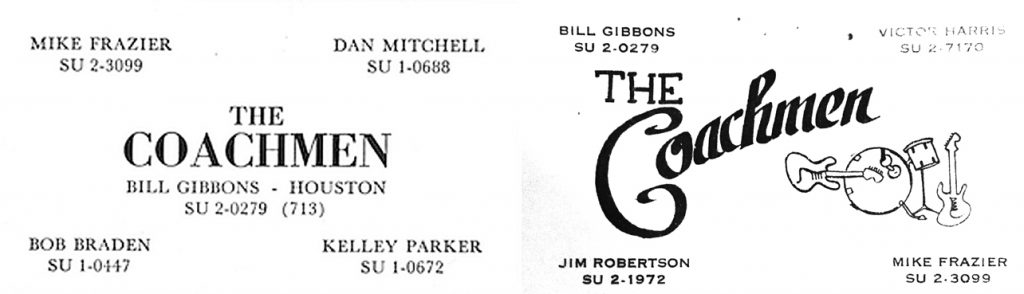

(Billy shows me a picture of a business card for The Coachmen, listing the personnel with their phone numbers, Billy written down as ‘Bill’ Gibbons)

SD!: That’s amazing. And these guys were school pals?

BG: All within the neighbourhood. We’d take turns torturing our parents in the garage. We’d go here, go there. (whiney teenage voice) “Please.”

SD!: Could we reproduce this in the magazine?

BG: Oh yeah, but you’ll have to add the ‘Y’. I was never a Bill, I was nevera Bill. That’s what comes in the mail.

SD!: Now, one of the Coachmen’s big influences was the 13th Floor Elevators, who you eventually became friends with.

BG: That was later. About 1967. The Elevators, they hit pretty hard, I want to say ’66. That was the first single, ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’. They were out there! And after The Coachmen, preceding The Moving Sidewalks, we added some horns. We had three saxophone players because Little Richard was our hero. His singing, I don’t think there’s been another rock & roll singer that can eclipse his singing. But his band came from Houston. The Grady Gaines Orchestra. Little Richard, he was from Macon, Georgia, I think. But Don Robey was a real astute black guy, businessman in Houston. He had two big nightclubs, The Bronze Peacock and The Eldorado Ballroom. He also ran The Buffalo Booking Agency. It was named after Buffalo Bayou which is the meandering river that runs through Houston. A real entrepreneur, this guy had it all covered. Gambling in the back, cops paid off in the front, cops paid off over here. And then later he acquired Duke Records and Peacock Records and believe it or not the original Duke and Peacock building, it’s a ghost of a shell, but it’s still in Houston, down on Rastus Street. So anyway, The Grady Gaines Orchestra, Don Robey signed Little Richard and he originally appeared on the Peacock label, which is more of a gospel label. But you can still hear some of those early Little Richard things – ‘Red Beans, Rice And Turnip Greens’, ‘Two Many Drivers At The Wheel’, they were secular, they were not gospel, but we took a page out of that book. We were called Billy G and the Ten Blue Flames, but we weren’t ten it just sounded good. I’ve got some posters, I’ll see if I can dig them out.

(An aside, it seems Billy’s getting his timeline a little mixed up, as most accounts report The Coachmen forming after Billy G and The Ten Blue Flames, not before).

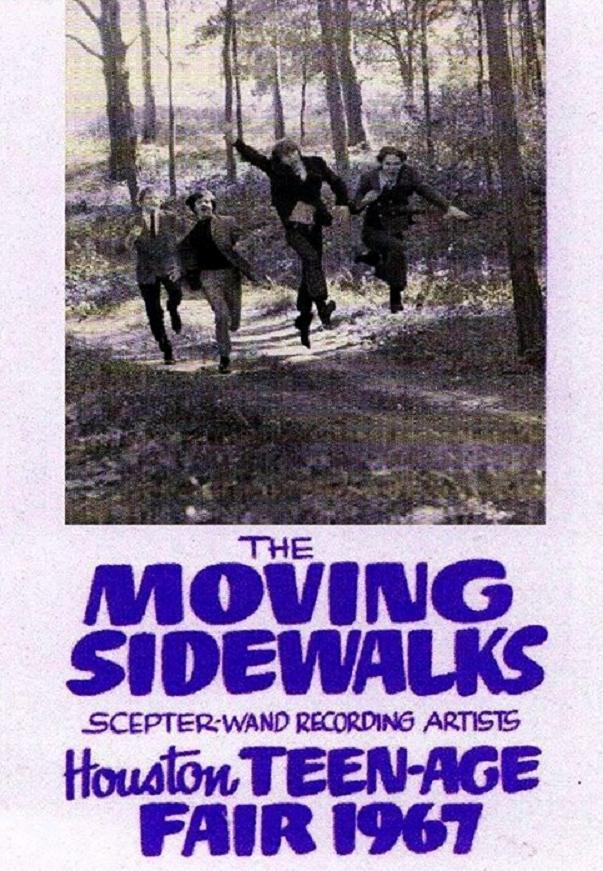

But then the Elevators hit with ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’, and I was like, “Oh My God, what is that?!” And there were two music rooms in Houston, one was called La Maison, which was a restructured abandoned church, there was that one. And downtown was the Love Street Light Circus Feelgood Machine. So we started going, and it was Tommy Hall on jug, we knew all the original guys, and Roky Erickson was leading the charge as the vocalist, Stacy Sutherland was on guitar, Benny Thurman was bass player and John Ike Walton was the drummer. And right in the early days, it was a tour de force, that scream was blood curdling, Roky. And that’s when we changed the name to The Moving Sidewalks. I thought well the Elevators, they’re going up, Moving Sidewalks goes forwards.

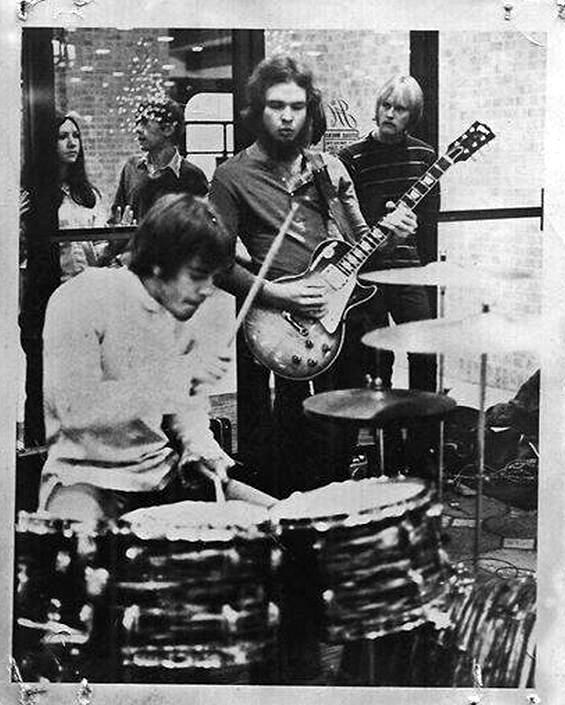

We stripped it down to four pieces. It was D.M. Mitchell, he was our drummer. Tommy Moore on keys, D.B. Summers on bass, and I was taking the guitar and vocals. And there was a large house, a big mansion in Houston. Unfortunately, urban development brought two major freeways that left this beautiful mansion on this abandoned island, a little pie shaped piece of property between these two new freeways. And it was a nightmare, the family moved out and it sat there vacant for a long time, and somebody came around and had the genius idea of turning this big mansion into little cubicles. Not even apartments, it was like a crash room here, a crash room there. But the Elevators moved in, as did the Sidewalks. And that’s what endeared us to the inner workings of Tommy Hall’s remarkable lyrics. It was more than a band at that time… well, I remember, the first few times I was able to see the Elevators at work, they did a James Brown number followed with a Buddy Holly number and then a Jimmy Reed number, and then they’d get into their own stuff which later solidified. That’s when it became philosophical. It was a musical presentation with Tommy Hall’s message.

SD!: And of course, it was a pretty psychedelic scene, right?

BG: Definitely. Oh yeah. I remember there was a kitchen that was shared. They had a refrigerator and an oven and the girls would come around and they’d take over the kitchen area, But I went in there one day and there was this nice cookie sheet in the oven, it was a complete sheet laden with weed being broiled. It was being sucked up into the rafters, completely encompassing the house, you could just walk around… so yeah. The word psychedelic I think had it roots in 1957, but Tommy Hall resurrected it as a tag, which the Elevators carried forward. Unfortunately they fell out of favour. Being any measure of forward thinking in Texas at that time was not a good thing. It was frightening to the establishment and that’s when the law stepped in. Ultimately the Elevators pulled stakes and moved to California and the Sidewalks followed suit months later. The heat was getting too oppressive and I’m not talking about the weather, you know what I mean (laughs).

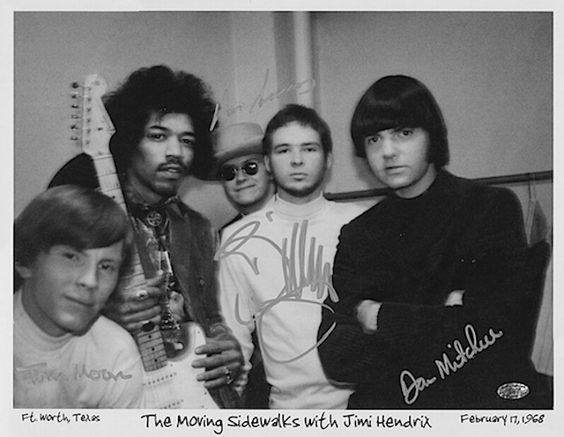

SD!: As well as the Elevators, you became pals with Jimi Hendrix. At what point did you come into his orbit?

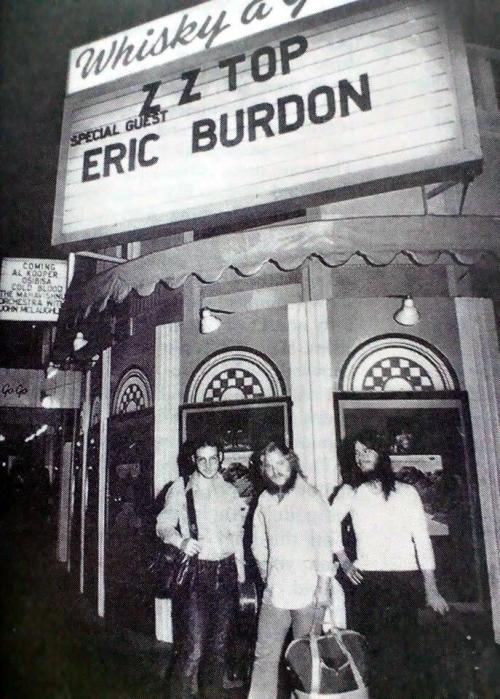

BG: The Elevators went north to San Francisco, we moved to LA, right there in West Hollywood. There were two great clubs, Gazzari’s and The Galaxy. Well, there was Pandora’s Box and… The Sunset Strip at that time… Was ’68 the so-called Summer of Love?

SD!: That was 1967.

BG: Yeah… well I remember that the four lanes of Sunset Boulevard had squeezed down to two because the outside lanes were just filled with people, constant cruising of the strip. Well, we came back to Texas, and that’s when the phone call arrived that said… Oh, a friend of mine had returned from London back to Houston. We had all gone back to Houston, and he had a copy of the first LP, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and it was just like, “What is this?!” It was such a ground-breaker, nothing had quite come across the grooves quite like this thing. So we started learning from this record. And we were slowly taking psychedelia, from the Elevators and now from this Hendrix Experience thing. And we actually attempted to learn a couple of the numbers. We played ‘Foxy Lady’ and ‘Purple Haze’. It was part of our little set. And we had a manager, we had a booking agent down there in Texas, and he said, “We’ve got this interesting offer, we’ve got this band from England who are planning on coming to the States and they’ve asked if you’d be interested in joining them, have you heard of this Hendrix experience?” I was like, “You’re kidding!” And when I say we learned ‘Foxy Lady’ and ‘Purple Haze’, we were contracted to play 40 minutes, and in order to play that solid, good 40 minutes, we played the Jimi Hendrix songs! And on opening night when we’re on stage, before he took the stage, we’re playing ‘Foxy Lady’ and ‘Purple Haze’! Over in the shadows, I see Jimi Hendrix with his arms folded putting the evil eye on us and when we came off stage he grabbed me and said, “I want to know you. I like you, you’ve got a lot of nerve!” (laughs).And that was the bonding moment!

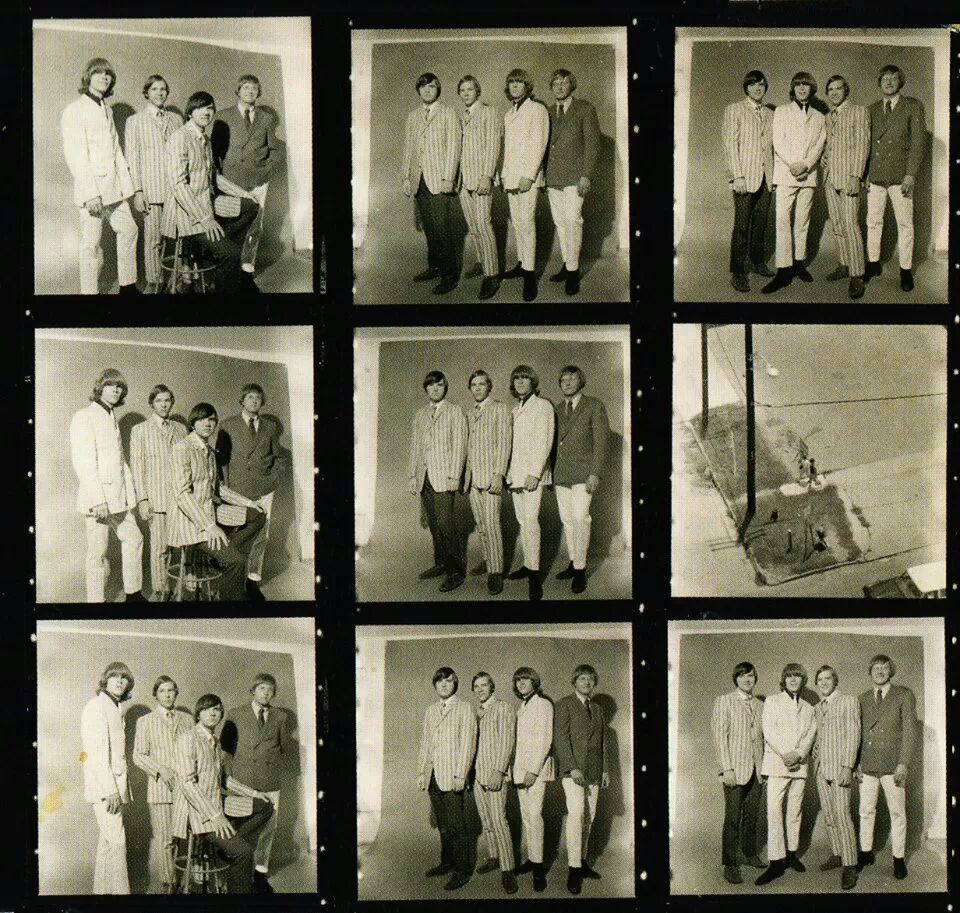

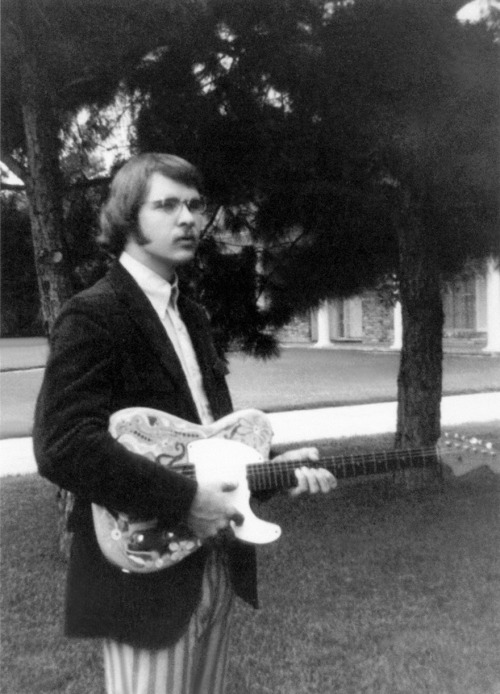

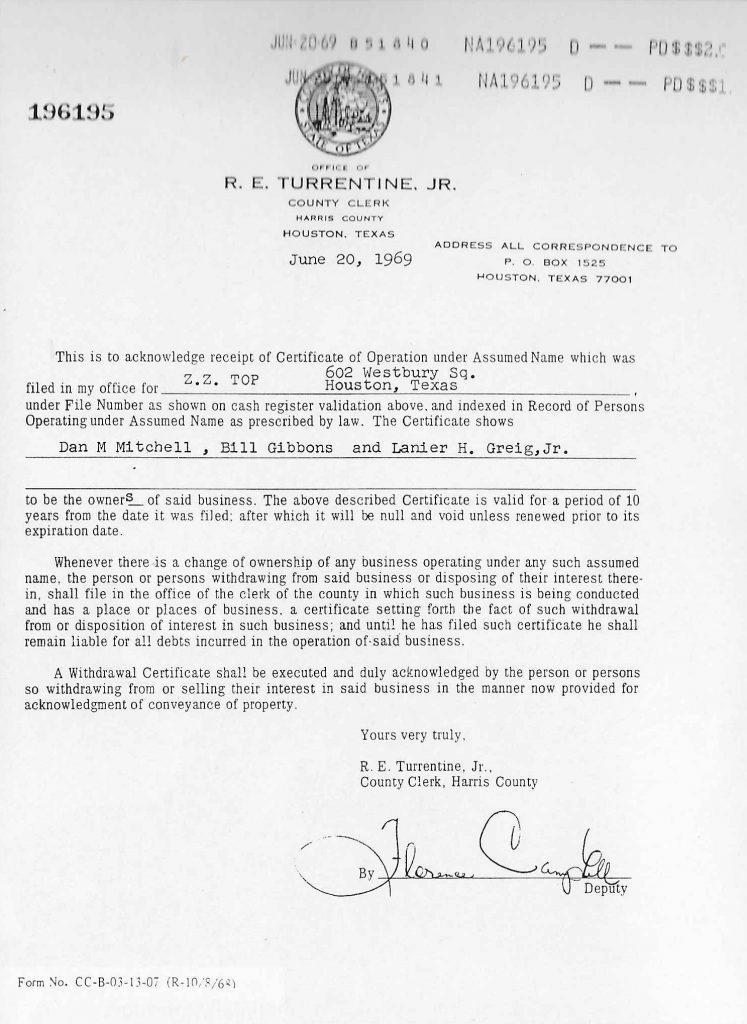

SD!: So tell me about how The Sidewalks turned into ZZ Top.

BG: The bass player and keyboard player, they had to bow out. But the drummer and I were determined to keep it going. There was another popular group there in Houston and they had a B3 player and we were managed by the same outfit. That was The Fanatics. Lanier Grieg was the keyboardist and what a talent. The guy had it! And we thought, Gee whiz, maybe we get along as a trio, The Moving Sidewalks, guitar, drums, B3 with bass pedals.

SD!: Did you plan on keeping the Sidewalks name?

BG: We didn’t know in the beginning. We kept the name Moving Sidewalks, and I said, “You know, maybe this deserves something else.” Because Lanier could emulate the B3 magic of Jimmy Smith, no small feat, I mean Lanier had it. So this jazz driven blues backbone started drawing us into the blues. Well I had this apartment that was lined with all these rainbow coloured posters that announced all of the soon-to-arrive blues players that were going to do a show in Houston. We’d go downtown and yank these posters off the pole. And I started noticing that many of the R&B artists of the day had initials for their name: DC Bender, OV Wright, BB King. And I thought BB King, yeah BB, and there was ZZ Hill. So I thought let’s take ZZ, that’s kind of unusual, and add it to King. ZZ King. Too close to BB King. But a king is at the top. So that’s the story you’ll get today!

But it was the transition, it was Mitchell, myself, and Lanier Greig and that’s when we decided to change the name and I threw out this ZZ Top and they said, “It sounds unusual, let’s start down another way.”

SD!: Tell me about the recording of your first single, ‘Salt Lick’.

BG: We did that in Houston. We did two sessions, one at Jones’ Recording, it was Doyle Jones’ Recording and one at Bill Quinn’s outfit, Gold Star Sound Services. And actually, you’re right, ‘99th Floor’ was first tracked with The Coachmen, way back, we were still in Junior High. Yeah, that’s right…

There were about four really top recording outfits in Houston. There was Doyle Jones, Jones Studio. Bill Quinn’s Gold Star, Bill Holford’s ACA and Walt Andrus, he ran Andrus Studios, and they handled most of the pop recordings. Blues guys… I mean Houston was a fascinating blues town. If you read the opening chapter of Ray Charles’ autobiography, he said, “If you want to put a good band together, go get your guys from Houston”. And somebody said, “What made Houston such a hotbed of talent?” Well there were two black high schools and the two music teachers were fiercely dedicated. And they used to say, “Look you’ve got two choices, you either excel in athletics or you’re going to learn how to play music.” And the guys that graduated under the tutelage of those two teachers turned out to be some of the greatest players.

But yeah, the released version of ‘99th Floor’, I want to say we did that at Andrus Studios. No, I take that back, we did it at Gold Star. But the reason I brought up Andrus is because Bobby Shad came down from New York City to hold auditions for groups. He was scouting out for new acts to put on the label Wand, which was a subsidiary of Sceptre, which was Flo Greenberg’s label out of New York. And a bunch of bands lined up, and the Sidewalks said, yeah, let’s go down and toss our hat in the ring. And we got picked. And that’s when we went in and rerecorded the released version of ‘99th Floor’. So yeah, interesting times!

SD!: Let’s go back to Lanier. He didn’t last long, right…?

BG: By this time. Summers and Moore, they went into the military. And we recruited… we stole Lanier out of the Fanatics. He was all gung ho. He said, “This is going to be tough, an organ driven trio.” And we did a couple of gigs together, and we parted ways with Lanier. He was called out to California. He had done an audition for an entertaining television show, which later became known as Mork and Mindy, and he got hired to play Mork.

SD!: Really?

BG: Yeah! But Lanier had this peculiar death wish, he’d find a way to trash all of these great opportunities. And I said, “listen man, you’ve landed the part for this television show, go!” Which he did, and then he figured out a way to trash that, and he was replaced by Robin Williams. And Lanier stayed out on the West Coast.

(It’s likely Billy is mixing up his dates here. Lanier did indeed eventually end up on the West Coast, and it’s possible that he auditioned for the part of Mork, but Mork & Mindy didn’t air until almost a decade later in 1978. Instead, contemporary accounts suggest Lanier headed East, where he tried out for TV pilot called The Cowboys).

In the meantime, Mitchell and I recruited Billy Ethridge, who was from Dallas, he played in The Chessmen – that was Jimmie Vaughn’s band with Doyle Bramhall, Tommy Carter was on bass. Ethridge played mostly rhythm guitar but he was also a very talented keyboardist. We initially thought Ethridge would take over the B3 and the bass pedals but he wanted to play bass guitar. That lasted for about… well we, hunkered down in a little ranch house outside of town and we wrote a number of originals…

SD!: And again Ethridge wasn’t long for the band…

BG: Ethridge wanted to, he actually decided after joining the group and playing bass, he said actually, “I want go back to playing B3.” So Ethridge left, he was replaced by another friend of ours, ‘Cadillac’ Johnson, a talented bass player. In the meantime, as Ethridge was leaving, he pulled me aside and said, “I know you like Jeff Beck.” And I had met Jeff Beck during The Moving Sidewalks days, when we still the original four. We’d landed some gigs when Beck was doing some dates in the states. And Ethridge said “Yeah I know you like that Jeff Beck Group”. And I said, “Well yeah, Rod Stewart sings like a bird, and Jeff of course.” What can you say? And Ronnie Wood was on bass but Mickey Waller was on drums and his playing was just… I heard it. In fact, I was attempting to style ZZ Top after seeing The Jeff Beck Group. And he said, “Well I’ve got this drummer, and I know you like your buddy Mitchell but why don’t you give this guy a try? Frank Beard, he’s coming down.” And I said, “Sure, why not? We’re just having a jam session.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9v0QZgwwLys

SD!: Did you know (Frank’s previous band) American Blues already?

BG: No! Which was really weird because they originated out of Dallas but they were resident in another joint in Houston called the Cellar. It was one of these after-hours clubs. They didn’t see the Sidewalks, nor did we see the American Blues. Except we saw each other on a television show, there was a Saturday morning teen show, The Larry Kane teen show. And I remember watching the American Blues on television and they saw The Moving Sidewalks on the same programme, which was an ironic awareness of each other, but we never really crossed.

SD!: Now I’ve got to skip ahead, because we’ve only got five minutes.

BG: Oh yeah, keep it coming!

SD!: Let’s jump ahead to finally getting together with Dusty.

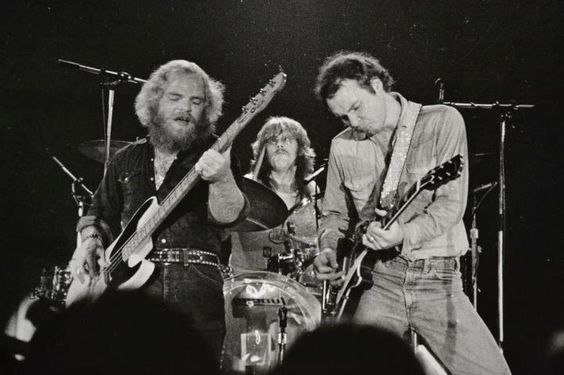

BG: The first day, I invited Frank to replace Mitchell and I don’t really like talking about that because it was very uncomfortable. Fortunately I made my amends with Mitchell years later. But I was 18 years old, I didn’t know. So we’ll leave it on the up. But Frank was a monster. And he said, “You know, he said the bass position is like a revolving door. But I’ve got a guy who I think might work. And he introduced me to Dusty. Which was really funny, the first day I met Dusty. Frank and I had moved into a house, and he said, “Yeah, Dusty’s coming at three, and I said, it’s noon, let’s just hang out. Four o’clock, five o’clock, six o’clock, there’s no Dusty. And there’s no cell phones, we didn’t even have a phone. We had no furniture. We had a television and a couple of mattresses. But Dusty finally showed up about 10 o’clock that night with a jug of wine, he came into the door and he looked at me and he said “I’m Dusty” and then he passed out. And I said, “I think this guy might work!” (huge laugh)

But the next day we got up and we lit the fuse. And as the story goes, it’s actually quite telling of the instant knowing it was going to work, we played a shuffle in the key of C for three hours straight. And I finally said, “This is going to work!” (laughs)

SD!: And then you were off and flying!

BG: Pretty much so. We did have some momentum, thanks to that first single ‘Salt Lick’, backed with ‘Miller’s Farm’.

SD!: And you were now working with Bill Ham, your manager and producing partner.

BG: Right. Bill Ham had stepped into the picture, and he had said, “You know I’ve been looking for a group, I like the sound you guys make, would you consider letting me take the reins and see if I can steer this in one way or another?” and I said “Sure.”

Billy’s PR pops his head around the corner to tell us we’ve got five minutes left. Billy requests an extra 15 minutes and a couple more beers, proclaiming: “The warmth I’m feeling on this whole excursion is excellent. We’re making good headway!”

Beers duly delivered, we return to the interview.

SD!: What were gigs like in those early days?

BG: We started in Texas and then there was a little club that had started just across the border in Louisiana called Willie Purples, down between Lafayette and Lake Charles. And Mike Pillot, a real Cajun, he ran the place and we actually started off, there was another joint called The Town House in Port Arthur, Texas, 90 miles outside of Houston, so we’d go east out of Houston, we’d stop at The Town House in Part Arthur. There was Port Arthur, Beaumont Groves. They called it this golden triangle. It was more like the Bermuda Triangle. And then we’d cross into Louisiana. And then the word started spreading and then we’d go to Mississippi.

The real turning point was a buddy of mine from Houston, Walter Baldwin, had gotten a scholarship to Memphis State, and he was rooming with a guy that fancied himself something of a promoter, and he’d put together a blues festival in Memphis. Now we’re talking ZZ Top’s First Album. I had sent it to Walter my buddy. It’s done and out. Walter unfortunately passed away recently but he was this unsung poet, a brilliant, artistically minded guy. And he called me up from Memphis and he had discovered Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, and he played it to me over the phone and I was listening and going “Wow”. And that inspired me to write ‘Just Got Back From Baby’s’, and once the record was out and pressed up and ready to go, I sent one up to Memphis and man, that fateful phone call, it brought the blues right out and his buddy, Steadman Matthews, was standing there and he said “Who’s that?” And he said, “It’s this group out of Texas.” And he said, “You know I’m putting on this blues show over at the Overton Park Bandshell”. It’s a miniature Hollywood Bowl, right there in Memphis. And he said, “I’d like to hire these guys,” so we took the gig. Piled in a car and drive from Houston to Memphis.

And Steadman thought we were black and when we turned up he sort of panicked because this was his blues show. BB King, Bobby Bland, Johnny Woods on harmonica, Furry Lewis was still alive. Well, he stacked the deck and he put ZZ Top at the very end of the show and he said, “Yeah, by this time, everyone will have gone and I’ll have saved face. I don’t need a bunch of white guys on this blues show.” But we delivered. It was a smoking hot set. After the show was over, that’s when I met Jim Dickinson, Robert Johnson, Lee Baker. These were the inner circle Memphis guys. And those are the guys that persuaded us, they said, “You know, you make fairly good records, but you might want to consider coming here to Memphis, we think that we could raise the bar.” And I said, “Well we seem to be doing OK in Texas, what’s up here in Memphis?” And they said, “Well we’ve got a great studio, Ardent Recording, why don’t you come by?” And I said “OK”. He says, “As a matter of fact there’s a good group, they play loud they play some kind of bluesy stuff like you do. I said, “Who is it?” He said, “It’s a group from England called Led Zeppelin.” I was going “Okay!” (huge laugh).

And that’s what started the residency in Memphis, from that. In 1973, we had already cut Tres Hombres in Texas. We took it to Memphis. Joe Hardy, Terry Manning, John Hampton, they were the three chief engineers and the release of Tres Hombres brought the single ‘La Grange’, which was the first Top Ten. And our manager was now convinced, now he’s sold. It was all his idea, of course. But we wound up staying in Memphis for the next 18 years.

SD!: Back then, did you experiment much in the studio, or did you go in pretty much ready to record?

BG: We had a little rehearsal room and in those days you wanted to make sure you had really done the proper woodshed. You didn’t want to waste a bunch of money trying to work something up. So we spent about six months just rehearsing and going over and refining because we wanted to hit it and quit it. But people say, “Oh yeah, we recorded it one week.” But it took six months to get to that one week! But I found Frank and Dusty. They had worked together in bands since they were teenagers so I had inherited this rhythm section, which was platformed. All I had to do was step in and start. But they were very talented as players and they had a passion for the song-writing thing, they really understood it…

The notion, turning the corner when 2019 rolls round, it heralds the 50th anniversary of ZZ Top, which is unthinkable. It’s only in the last couple of months that it rang our bell. We woke up and some guy said, “Hey what are you doing to celebrate 50 years together?” It was like a cold shot. 50 years, where did it go?

SD!: Are plans coming together to celebrate the 50th?

BG: I suspect there will be a move afoot in the not too distant future to put something celebratory together. As you pointed out, when you’re passionate about your work, it ain’t work. And somebody said, “What’s the secret, you’ve kept this band together for 50 years, longer than most marriages last?” I said it’s simple. Two words. Separate buses! (laughs)

We still enjoy getting to do what we get to do more than anything else. And I believe that’s behind the surprise realisation that it’s been a rather admirable length of time. But it doesn’t seem like it, it seems like it was yesterday. There’s another point, we call it going to the Bahamas. Every night we take that deck, we step onto the stage never knowing who’s going to make the first mistake, and all of a sudden… Getting to the Bahamas is one thing, getting back is the real trick!

SD!: Was there ever a moment when you realised ZZ Top were now famous?

BG: I would roll back to 1983. As you know MTV was uncharted territory, nobody knew what to make of it. They didn’t know if it was going to catch on, the record companies didn’t want to spend any money. “Video, what is this thing?” The first three videos we did within the space of a year. ’83, when Eliminator was released, was followed by ‘Gimmie All Your Loving’, ‘Sharp Dressed Man’, and ‘Legs’ was the third video. And we were in London. I guess the BBC had decided to do an all-night broadcast of these video things. And they played all three ZZ Top videos as the pubs were letting out. And then it was on. It was like “Who the hell are these guys?!”

SD!: What keeps bringing you back to the blues?

BG: As you may know, the preceding solo work, the first one, was actually aimed to penetrate the enthusiasm of the fans in Havana, Cuba. We had received an invitation to perform at the Havana Jazz Festival. And I said, “Well, let me ask my two partners,” and they said, “No, no, they just want you.” And I said, “Hmm, I don’t want to crash a jazz festival with a rock ’n’ roll party, let’s see if we can Cubanize, Gibbonize, ZZize whatever,” and Perfectomundo was the result. And unexpectedly it received a rather admirable amount of success, which prompted John Burk over at Concord to say, “Listen, we’ve done a Cuban thing, went down, played Havana, put the road show together. Could I persuade you to turn back towards the blues, something bluesy?” And I raised my right hand and said, “That’s where we started, that’s where I stand.” And he grinned and I said, “Let’s give it a shot”. So with that bit of urgence…

And then of course, as I mentioned, not only had Greg Morrow shown up and taken his place behind the drums, James Harmon, the great Harmonica player, he was in from California and he stopped in, so it was a party.

SD!: How impromptu were the recordings?

BG: Well, after the third day, when we realised that Joe had captured some rather interesting and appealing starter pieces, it prompted me. I said, “Man, maybe this is the way to go.” I grabbed pencil and paper and started attempting to put my mind where Howlin’ Wolf may have lived once, or Muddy Waters, you know, the whole gang. And I want to say, we wrapped this up in short order, but with that rather natural beginning, once that ball started rolling up Blues Avenue, we embraced the feeling. And I think it’s pretty fair to say, if you’re having good times in the studio, they tend to show up in the grooves and that’s pretty much it.

The Big Bad Blues is out now on Snakefarm Records

For the full story of ZZ Top’s early years, pick up Shindig! issue £85, in UK shops November 1st or order via our shop