Matt Berry talks with Shindig! ahead of the release of his new album, The Blue Elephant

Since signing to Acid Jazz Records in 2010, MATT BERRY has become the most prolific artist in the label’s history, releasing eight albums throughout a 10-year period. He began that decade as a little-known comedic actor whose homemade recordings had rarely been heard outside of his inner circle; at its conclusion, he was a BAFTA winner (for Toast Of London) who had drawn international acclaim for a hugely ambitious discography that evinces, with often jaw-dropping sonic detail, a near-lifelong love of psychedelia, prog and folk-rock. (It makes sense that one of his first albums was a gifted copy of The Complete Mike Oldfield.)

This month, Berry releases yet another album, less than a year after its predecessor: the suite-like psychedelic opus The Blue Elephant, which was recorded entirely during lockdown. (Berry self-produced and played every instrument except drums.) As part of our history of Acid Jazz (in issue #116), Berry spoke to MICHAEL WHITE from Toronto, where he was filming the Emmy-nominated series What We Do in The Shadows

Shindig!: What was your relationship to Acid Jazz before signing to them? Were you a long-time fan?

Mattt Berry: I was a huge fan, for lots of reasons. One was, you’ve got to remember this was back in the ’90s, when it wasn’t easy to get every kind of record you wanted. I was into Hammond organ and groove stuff – ’60s stuff, psych stuff – and it was impossible to get hold of that unless you went crate digging, and I was in Nottingham. You could do that [there], but luckily there was the Acid Jazz label, which had all of that stuff in terms of compilations, [especially] Hammond Street and the Rare Mod series. And I continued to be a fan because the great thing about Acid Jazz is, the sort of music they champion and sign, it’s all very timeless. The label’s never been uncool or gone out of fashion, as far as I’m concerned.

SD!: How did you come to their attention?

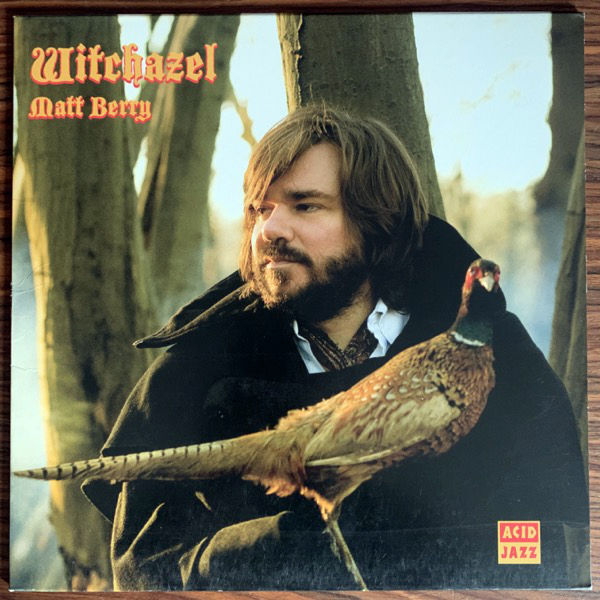

MB: It was through a mutual friend. He heard I’d made this folk album – this is about 2009 – and he said, “You know, I think [Acid Jazz co-founder] Eddie Piller might be interested in this.” I was like, “Really?” I’d just recorded it all myself, for myself. I was just going to put it out free on the internet. I never told Eddie I was a fan of the label and a fan of him, and it’s a good job because he has the biggest head [laughs], so it wouldn’t have done any good at all if I’d have told him that.

So, I went down there, and we sat looking at each other while he played my whole album, and I thought, “If he doesn’t like it, fair enough.” He didn’t have any pre-existing knowledge of me whatsoever; he hadn’t seen anything I’d done on the TV either. We got to the end of the album and he’s like, “Yeah, let’s do this. Let’s do the whole album.” And I was like, “Jesus Christ!” [The album was released as Witchhazel in 2011.] Honestly, I didn’t expect it. I already had the front cover, I’d mixed and mastered it myself, so he didn’t really have to do anything. The rest is kind of history. There hasn’t been more than a couple of days since that we haven’t spoken to each other. We immediately got on that day, and I kind of knew that I’d be continuing the journey with this guy. I knew this guy would be in my life most days from now on, and that’s the way it’s been. He and Dean [Rudland, label director] have been everything in terms of my musical outlet. They’ve backed me in every single thing I’ve wanted to do.

SD!: Eddie told me he contemplated shutting down the label multiple times over the last 10 years – particularly after he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2013 – and he gives you much of the credit for convincing him to continue.

MB:When he didn’t have the energy to continue with it for lots of reasons – one of which was that he wasn’t very well, and there wasn’t much money around – I was in the office and I said, “You don’t know what this label looks like to everyone else. To me it’s as important as any other record label. It can’t end. There’s much more life in it, and I’m very confident that you’re gonna get through this and the label will continue.” (Note: Piller made a full recovery.)

SD!: You’re inarguably the most prolific artist Acid Jazz has ever had. You’re so clearly a fan of all sorts of music from a point in history when it was standard practice that a band would release an album every year, or sometimes more often than that. Is that partly what motivates you to be as productive as you are?

MB: No. It’s because I have the ideas and I just need to record them. It’s as simple as that: having an idea or wanting to try a different style, a different way of recording. Because it’s up to [the label] whether they put it out of not. I’m going to record it anyway. If they’re into it, fantastic. If they’re not, it doesn’t matter because it’s something I wanted to get off my chest, so to speak. If I have an idea, I need to get it down before I totally forget it or I move on to the next thing.

SD!: The Blue Elephant is coming out less than a year after Phantom Birds. When did you start work on it?

MB: I started it when I was promoting Phantom Birds, this time last year [Spring 2020]. I was basically promoting my last album while recording this one. My head was in two different places: I had to talk about Phantom Birds, yet I was basically finished with all that and had completely moved on to something else. I finished it at the end of the year.

SD!: Did the pandemic end up being of benefit to you, in terms of your productivity?

MB: Probably. I wouldn’t have been able to spend much time on the small details, which are always important, especially with something like this. I think the fact that I immersed myself in it and had nothing else to really get in its way – it’s one of the albums that I can say I spent a hell of a lot of time on.

SD!: Something I immediately like about this album is that, even more so than what you’ve done before, it seems to actively discourage passive listening. I wonder if that was part of your intention, to try to will back a time when people routinely would put on an album and not do anything else while listening to it from beginning to end?

MB: I would hope that everything I’ve recorded is to discourage passive listening. If you’re a passive listener, I don’t think you’d be going anywhere near anything on Acid Jazz. You’d just be having the radio on quietly.

But you’ve kind of hit the nail on the head. Part of the intention of it is to be listened to with your headphones, in the same way that I did with [Jeff Wayne’s] War Of The Worlds or the original album of Jesus Christ Superstar. It’s got to be an intense, atmospheric sort of experience. That was one of my intentions with The Blue Elephant. It isn’t something you can switch off with. It’s going to change gears fairly rapidly at different points.

SD!: I’m glad you mentioned headphones, because this is such a headphones record. Did you spend a particularly long time mixing it?

MB: Yes. I spent a long time on the mixing and mastering. Even incorporating the old-fashioned ways of doing stuff – like, there’s three moments on the album where the whole of the song goes through a sort of flange/phaser effect, which is what they used on ‘Itchycoo Park’ by The Small Faces, that sort of thing. I had to do some research and basically find out how they did all that, in order for it to sound analogue and as good as it could. I didn’t want it to be a digital plug-in version of it. It had to be done the authentic way. If I hadn’t had the amount of time that I did have, I couldn’t have done all those things, I don’t think… Doing things the old-fashioned way – actually, no, the manual way – that’s what I’ve always tried to do.

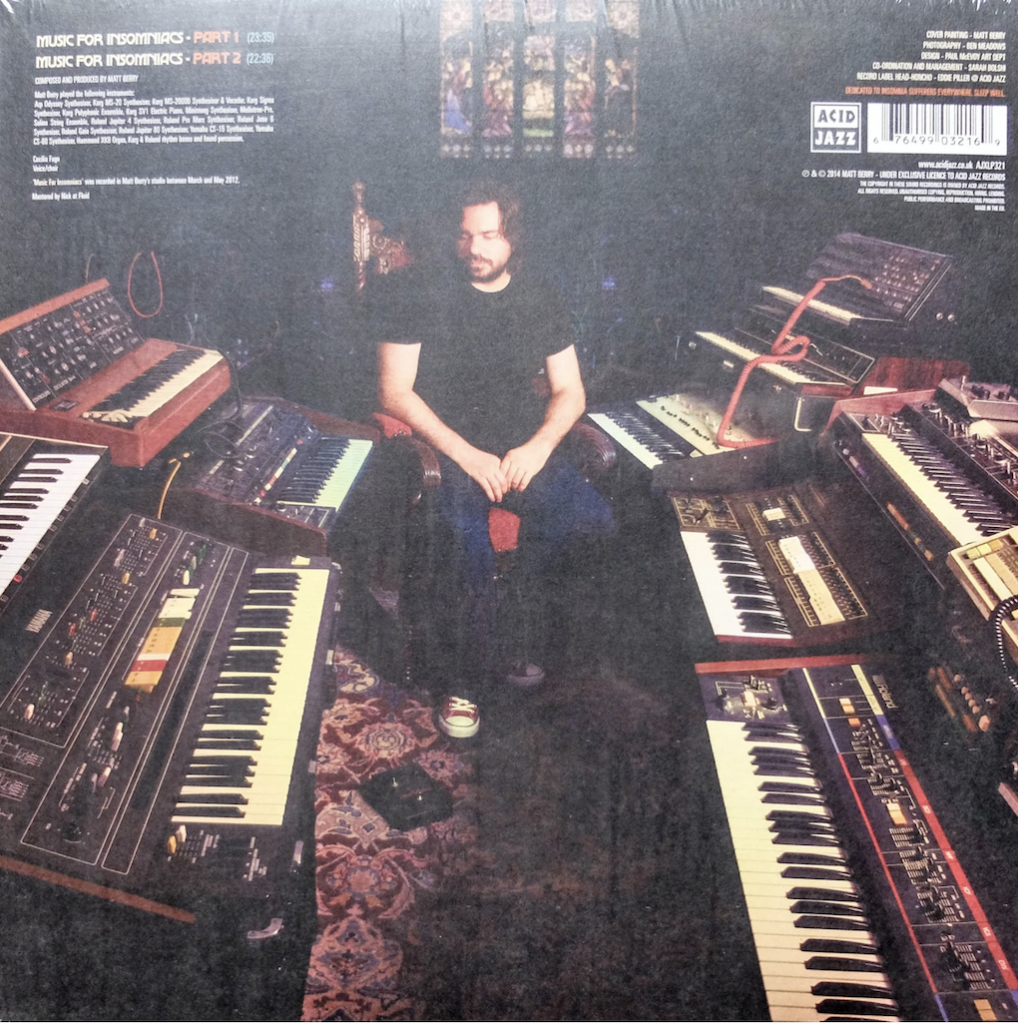

SD!: Have you managed over the years to acquire all of the technology that allows you to achieve this sort of result?

MB: Not all of it but some of it, mainly because when I bought a lot of this stuff, it wasn’t very fashionable, and therefore it wasn’t as expensive as it is now. I bought a lot of these organs in the early ’90s while I was working in a supermarket because they were, like, 100 quid each. It wasn’t digital, so everyone thought it was shit. And it “didn’t look cool,” whereas I thought it looked very cool. I mean, it can be a pain in the ass, because a lot of this stuff breaks down. But every piece of gear sounds slightly different from the other one, which is why it’s better to do that than use something which is in the [digital] box, which always sounds the same for everyone. I don’t want to sound like everyone else who uses the plug-in.

SD!: Were there particular albums you were referring to as sort of sonic touchstones?

MB: Anything that was recorded during that golden period of record production, from the late ’60s to the mid-70s. That’s my benchmark, that time. All of the releases that I’m into were more than likely recorded during that time, starting with The Doors’ first album until [Jean-Michel Jarre’s] Oxygène in 1976. For instance, you’ve got The Doors’ first album in ’67, which, compared to The Dark Side Of The Moon – you can see how much it’s evolved. And it’s that time in between that I’m interested in.

The Blue Elephant is out 14th May on Acid Jazz