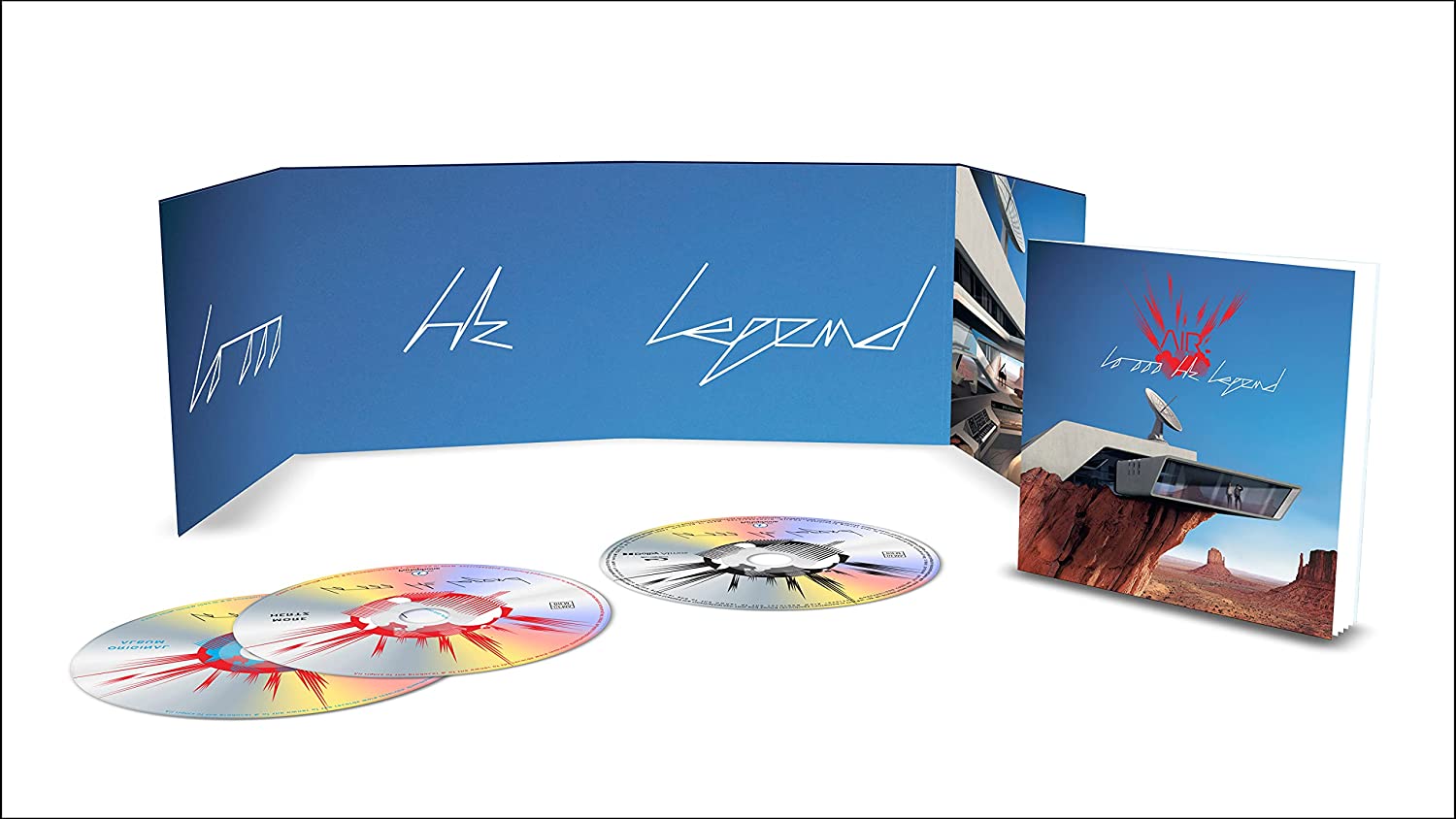

Air’s ‘10 000 Hz Legend’

JON ‘MOJO’ MILLS spent an afternoon chatting with Nicolas Godin and Jean-Benoît Dunckel about AIR’s difficult sophomore album, 10 000 Hz Legend for issue #123‘s Family Album. As so much was discussed that wasn’t included in the article, here’s an extended piece based on the interviews

Nicolas Godin: Moon Safari was such a massive success, the record company urged us to support it by touring, which was something I had never done. We were at a party at The Chateau Marmont and Beck was there with Roger Manning, and we were chatting on the terrace. I explained that we were going to go on tour and I did not know what to do, so all of these guys said, “Yeah, we will come and play with you,” which was a nice offer. That’s how we decided to set up a band in LA to tour with, but I was completely lost in this. It was a very big shock for me to have this kind of lifestyle.

Jean-Benoît Dunckel: We had played with them on stage the previous year when we were touring Moon Safari, so we knew them really well. We let them free when they played in the studio, more so than when they played with Beck.

NG: Air was really the cool thing in LA in 1998. We were like the city’s darlings. All these guys really loved old keyboards and synthesisers. For some reason, JB and me are very good with vintage synths, as we use them in a very novel way, a very romantic way. These people understood the poetry we put in these keyboards and they wanted to be part of this as well. There was a nice connection between us. We were all analogue keyboards lovers, soundtrack lovers, and Brian Reitzell was a music supervisor, which meant he was into the soundtrack world, and Brian Kehew and Roger Manning had a group called The Moog Cookbook, so they were into keyboards, and Beck is very Francophile, he loves the French life in Paris, and we are from Versailles with that rich history of Marie Antoinette, which he found fascinating. It was the same for us too with them when we were in LA, as we grew up with all of these TV shows, and Logan’s Run was shot just outside of LA… so for us when I arrived in LA I was in my TV set. It was a win win… we were giving them the romantic French lifestyle and they were giving us the LA TV show dream that we grew up with. We had a common ground.

I did the classic move in terms of making my first album and it being a big success, and for some reason I didn’t trust myself as a “real musician”, but I didn’t understand that my weakness as a musician was my strength, which is how I created Moon Safari, making the most of my limitations… and I could have done 10,000 hz with my limitation one more time, but as I had access to all of these great musicians, I said, “For this album there will be no limitation, I’ll just stay with the best people.”

The Virgin Suicides was recorded in a studio in Versailles, and then we moved to Paris to live and didn’t want to commute, so we looked for a space that was a soundproof environment where we could set up our gear. We found a studio in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, one of the nicest areas of Paris, which was brilliant, as recording studios are usually in a creaky old suburb, but this little studio was in the middle of the cool area.

We had no songs in our bags when we entered the studio. Everything was created in the studio after The Virgin Suicides and I had a big anxiety in because as the success of Air had been phenomenal. I think this album is a pretty tortured album, as it was a dark time for me. In a couple of months I was in this big pop music act going around the world and selling millions of records. Moon Safari was my first album and I was an architectural student.

Everything was new to me.

There’s a darkness in both albums. I think we went back to happiness with Talkie-Walkie. They were dark times and I was happy when it was over. Everything was shiny again, so it was pretty cool.

The music is the child part of us, so there’s this freshness and innocence in whatever we do, because my main goal when going into a studio is to be spontaneous and not to be part of the outside world.

We started recording everything in Paris, and then after a month, we rented the studio for composing and researching the sound. Beck came to Paris to promote his new album Midnite Vultures, with all his band, with Justin, Roger and Brian, and Brian was there to also work on a soundtrack thing for a movie, and after Beck was gone the musicians stayed in Paris, so all of these guys from LA decided to record with us. We did all of the bare bones here, sitting in a room, messing around.

I really liked to be surprised by them. I’m not a guy who thinks the best music is your own music, I like it when albums are made with a different energy. For example, if you listen to a Brian Eno album or aRyuichi Sakamato album it’s just one energy, and I miss something. I like albums with several energies.

I’m a big fan of Japan. When I land there I am the happiest man on earth. There’s a big relationship between Japan and Versailles, I think the gardens of the palace they are very zen. The architecture I grew up with is very zen and all this music I do I try and find this perfect balance between emptiness and fullness. We met Yumiko [of Buffalo Daughter, which is how she performed on the record] because we had common friends with Mike Mills and The Beastie Boys’ label, Grand Royal, so we socialised with the same group of people really.

The mixer Tony Hoffer he processed the sounds very well at the end. I come from the home studio world, so I used to record everything myself. I don’t think I fully appreciated the roles of the collaborators. They did a great job, but maybe I didn’t know how hard it was to make a record sound so great, as I had no experience. We were lucky to work with such brilliant people.

JB: When we were in Paris we had a young sound engineer who would record us on a console which gave us a nice analogue resonance… after that all of the recording in the Capitol Studio in LA with all of the amazing engineers was incredible.

This was the first album we had recorded on Pro-Tools and we had a special engineer in Bruce Keen. We needed him to synchronise everything, as there were so many tracks. It was a new technology and there were a lot of problems sometimes with the plug-ins not working. It was risky, but we wanted to use the incredible easy way of editing, cutting tracks and mixing them. We wanted to experiment with all of the new digital things as well as the old.

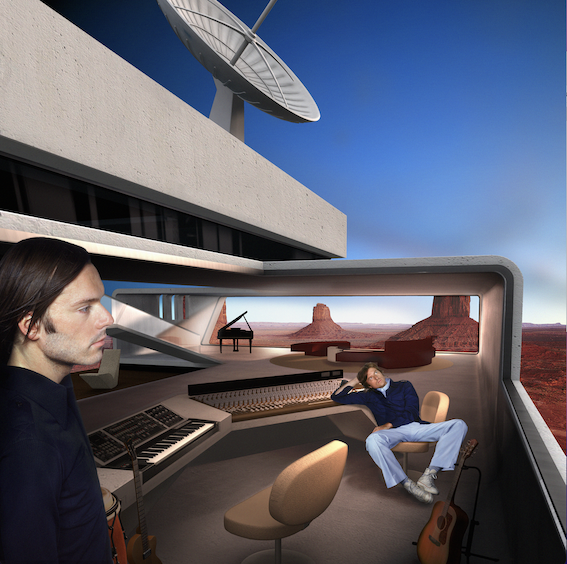

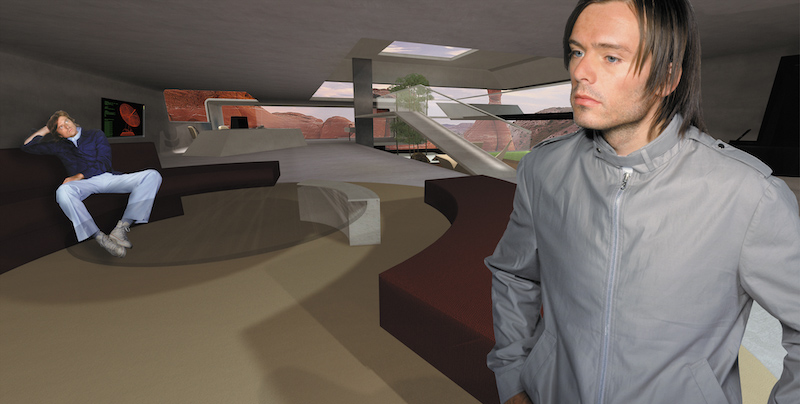

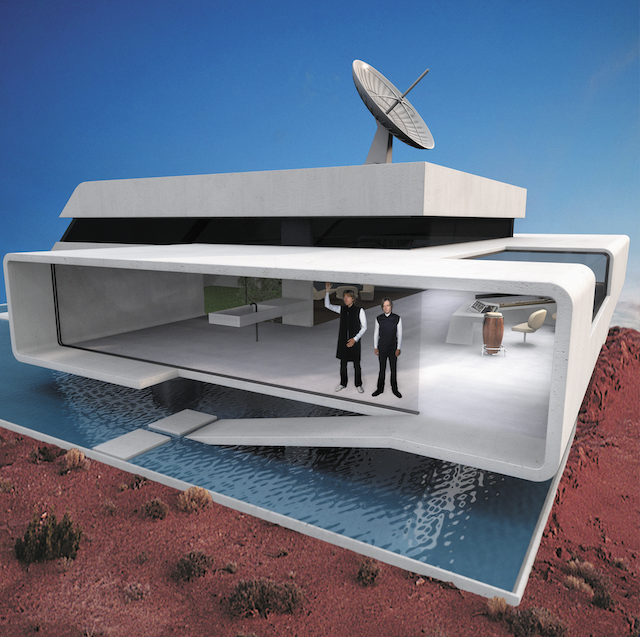

NG: Ito Morabito did the album’s art. He listened to the album and the cover art was his decision. He was 18 years old when he did that.. I belong to a generation when I was a child in the ’70s and we were talking about the year 2000 when I was a child, so my generation is very much influenced by retro-futurism… we were talking about dressing in silver suits and being in space ships, but nothing really happened, yet 2000 was such a big symbol when I was young. When we were recording 10 000hz it was actually the year 2000, and of all our dreams nothing happened really. We just had the internet, so instead of going into space we were just staying home on our computers. It was kind of depressing. The only technology that was in the cartoons I watched as a child was the FaceTime video. That was the only thing that occurred, none of my other dreams happened. So this house on the cover was to relieve that dream… It was a very short window, as the people from the generation after me they had not been raised in that dream or era

JB: On the cover you see the dessert in California and we are locked in a little studio in the middle of nowhere. I think the music is like a call of being lost. We were feeling a bit lost actually during this time. We felt like were not understood well by the media. For example, when you do an album after having some success you realise you are well-known and loved, which you didn’t really expect to happen… and you just realise that you are not understood. We wanted to send a message out to our fans and the media that we wanted to be deep and we didn’t especially want to be famous and played on the radio. We wanted to create a unique piece of art.

Having Beck sing on the album on ‘The Vagabond’ was part of that. It was a new universe for us. It was an American Western universe that we’d discovered at this time. We would also discover it by travelling into The Wild West on our tour bus. It was all attached to this mood of discovering the mid-west and California, so we wanted to have that in a song, and Beck had this culture in his blood, so it was like magic.

In our life, especially mine, the album also marked a sort of breaking away from my family. There was this feeling that the love and the harmony was breaking up. I felt like a lost man that was away from his family, and he was loved, but the love doesn’t work anymore.

At this age we were meeting the world and when we came back home we were like somebody new, somebody else; especially our wives knew that we were completely disconnected. We were so French before and we only knew the Parisian attitude and suddenly we were projected into the world. We discovered a new culture. People in California were more open-minded and curious about things.

The mentality was very different. In 2000, England was exploding and the world was more free. This was just before 7th July 2001. The feeling was we were all brothers and we all wanted to make a more open world, and we were going to be one nation of brotherhood. But it changed.

NG: As well as recording in Paris we recorded at The Bomb Factory in LA, because of the gear – it had the best collection of old synthesisers, and it was like being in a candy shop. We then went to Capitol Records to record all of the classic instruments, like the violins, choir, flute, harp… and then we recorded everything else in Hollywood Sound, all of the guest vocals and all of the guest musicians. It was pretty cool.

At the time there were no limits in the budget, not like now. We were flying first class to LA and we stayed for weeks in gigantic hotel rooms at The Chateau Marmont, we were in the best recording studios with no limit on time or budget… we could hire choir, an orchestra… it was fucking bad ass… we had the harp player from Pet Sounds playing on ‘Radian’.

JB: There was this album by Lee Hazlewood & Nancy Sinatra, I had a ‘Best Of’, and I think they recorded in the same studio, Capitol, where they also did a lot of Frank Sinatra and movie soundtracks, and so that’s why ‘Wonder Milky Bitch’ sound like it does.

With Serge Gainsbourg and Lee Hazlewood there is the narrative in the song that tells a story. It’s another kind of a level of song, it’s very poetic and pop.

With 10 0000 Hz, after Moon Safari being really big, it was time for us to do something really deep. We knew and felt that it was our time. We also knew that we would disappoint people a lot as they loved “the Moon Safari sound”, which was really loungey and spaced-out, but also a little bit childlike and comfortable, but with this album we really wanted to experiment with something deep, mixing in some deep textures of electronic keyboards with amazing orchestras and creating some unformatted formats of songs. For example, ‘Radian’ is three songs together.

NG: I think the intro and the outro of ‘Radian’ are a little bit too long, but that’s the thing with 10 000 Hz, the structures of the songs are a little bit too complicated. That’s why I love ‘How Does It Make You Feel’ as it has a very simple structure. When we were in the studio we were doing crazy experimental stuff with ‘Electronic Performer’, ‘Don’t Be Light’ etc and when Brian Reitzell came he was very surprised that we were doing this, as he was a big fan of Moon Safari, and he said to us, “But don’t you want to do something with beautiful Air chords, something you were good at?” So to please him we sat in the studio and we composed ‘Radian’. Brian played the drums on it and that’s how ‘Radian’ was made. It was a request from him to do more Air-like chords and vibes.

We always had a problem with the drums because the way we were working, for example with this song, me and JB we were playing when he was recording, and we then added some stuff on the song and we realised that after adding more layers the drums were not loud enough, but it was too late. The same thing with ‘People In The City’ where he played drums with me on guitar and JB on keys, and it was quite nice like that. Then suddenly we add all of this stuff, I add fuzz bass and stuff, and the drums are too quiet. That’s a problem I couldn’t solve really as I couldn’t think what the music would be like at the end. We should have maybe thought about this when we did all of the arrangements. Then the energy was gone.

JB: This was the first album we had recorded on Pro-Tools and we had a special engineer in Bruce Keen. We needed him to synchronise everything, as there were so many tracks. It was a new technology and there were a lot of problems, sometimes with the plug-ins not working. It was risky, but we wanted to use the incredible easy way of editing, cutting tracks and mixing them. We wanted to experiment with all of the new digital things as well as the old.

There’s a ’70s feel though because of the drums and the keyboards. We were obsessed by the sound of the drums and we wanted them to sound deep and dry. Real drums are played, so it gives a ’70s rock feeling.

We didn’t want to make a 2000 album. We wanted to make an album for the future.

It’s all about having a story to tell and feelings and emotions in the melodies that speak to your gut. The mystery of being lost in your universe.

We wanted to make something that you don’t control too much and is higher than us. An artist is an artist when you are able to do that and capture this mystery of music.

NG: That’s my obsession. When I make music my goal is always to make timeless music. I don’t listen to my own music at home, and haven’t heard this since then. We added some digital keyboards and new technology plug-ins. We always like to mix things together and don’t think we are obsessed by the past. Even when I did when I did Moon Safari I was mixing Ennio Morricone with Kraftwerk. I love to mix different textures together. I love old gear as it sounds amazing, but I also like new technology. Every year I was in the music shop and buying the new gear that was just released. I was excited about new technology all the time.

I just had a baby which was new for me, and that kept me busy, and it was the very beginning of this new technology, like Pro Tools. We had all these gadgets. And of course we were still watching all of the old sci-fi movies like Escape From New York, and were in that fantasy world.

When you listen to the album the first sound that you hear is a bit I made with a Korg electribe R1. It was brand new, and very organic, as you can touch the notes with your fingers. So we did a lot of stuff with the little drum machine on the album. It’s a drum machine that I’d never have used on Moon Safari though. It was very modern.

The biggest thing on the album though is the Memory Moog, which we bought in LA when we did the promotion for Moon Safari. We went in Black Market Music on La Cienga Blvd and we became a friend with the guy who worked there, Brian Kehew from The Moog Cookbook, and we bought this Memory Moog in the store that used to belong to Motley Crue. We went back to Paris, and it was time to record 10 000 Hz, so we plugged it in. Basically, a lot of the sounds were from the Motley Crue presets on the keyboard.

JB: Old synthesisers are living things, you can’t really control them actually. The vintage Moogs have a lot of possibilities. In the ’70s they used to use them in a special way, but there are so many ways, and so many sounds that are possible, and you just have to make them happen.

NG: We had new MacBooks too, which were a new thing at the time. There was this little voice menu where you could type text and it would talk. I think it was the “whisper” preset, and we thought it was funny. We were just in the studio messing around, which was really natural behaviour.

We cut ‘How Does It Feel’ after visiting the catacomb in Paris where we saw thousands of skeletons. It was a Friday, we cut the track, and JB had to leave the studio at 4 to get his kid at school, so I said to Roger, Justin and Brian, “Let’s do something,” and we went out of the studio to visit the catacombs, and they were very impressed… and then we came back, and Roger said “Let the song play” and he did 12 tracks of vocals and JB came back at 2200 after dinner, completed the vocals and the song was completed at midnight.

JB: On the first part, the verse part, there were some chords that were melancholic, and sad and dark, but I had this sort of John Lennon chorus, so I felt like putting some light in the chorus mixed with a dark verse that would produce, in terms of composition, a surprise. The chorus was too pop, the verse had to be cinematic and strange. In terms of music the two go well together. The real voices had been made by me playing the chords on my mellotron and we copied that to make it playback like a choir. Also we put a chorus pedal on the Rhodes that I played with Brian directly on the blueprint and the drum, especially the snare, has become famous in the electronic world, and I won’t say the name of the band, but they have sampled it many times. They said to me it is one of the best snare drums they have heard. And it’s a really well-known band, so I know this song has some reference for electronic musicians as the drum is so fat.

NG: ‘Don’t Be Light’ was the second song from the sessions, ‘Electronic Performers’ was the first. On each album there is also always a song that could have belonged to the previous album. It’s kind of a rule. That’s ‘Don’t Be Light’.

JB: The ‘Don’t Be Light’ fuzz bass solo is played by Justin, and he was really, really good to play like that, as he was crazy. He played really well. We wanted to catch this unique vibe on the record. He did something really rocky.

My favourite song though is ‘Caramel Prisoner’. The way the song is composed is very unique. I remember how we recorded this song in Paris. We had a cycle of 12 chords played together and I sung and tried to make track by track some harmonies with my voice over the chords, and then we would record that on the special hard drive machine, which was not a computer, and there were 16 tracks on each, so I maybe recorded 12 tracks of voices and on the four other tracks there were guitars and maybe a Rhodes and something rhythmic to keep the tempo, and on this machine there was a special switch, and if you put the switch on the left it was playing backwards and pitched down and reversed, so we took the voices, and then with my ears I tried to relisten to the chord that it would make, and then on the score I wrote down the new harmonies that I would hear. We then expanded the instruments, but the initial process was really random as it was based on some mistaken reversed harmonies.

NG: The Memory Moog is the only keyboard we use on the album with the pads of the [Roland] VP-330, we composed that track and didn’t think it was that great, and we then reversed it, and the chords were interesting. Then we took a piece of paper and we noted the score and we then learnt how to play the song backwards and we re-recorded the backwards version, but the right way round, so there was a transformation, which was a very funny process.

JB: The album took about one year… Nine months in Paris, recording the sketches and then we went to LA and we recorded over month and a half, and then went back and mixed it and maybe recorded a few things and that was it. But there was a lot of time in the studio trying to make it happen and recording different types of compositions. It was hard work as we were recording every day.

NG: It felt like a flop when it came out really. We didn’t have any big single, the record company didn’t understand what we had done, and then for the next album Nigel Godrich put us back on the map for commercial success. When your third album is a success it means you are there forever. We really under performed with 10 000 Hz, but if we would have done something more in the style of Moon Safari I don’t think I’d be here today talking with you.

JB: I think this is the experimental album of Air and this album opened some different kind of windows for the band. The thing which is really weird is that when [French band] Phoenix listened to the album they asked what the title meant, and I didn’t really know. When I thought about this title I wanted to have something mysterious and that you can’t really understand. I read a Hitchcock book and he talks about how in his movies he would get people to think that maybe there was a reason, but there wasn’t and you don’t know what it is. The 10 000 Hz Legend doesn’t mean anything, and there is no reason or a special story, but the strange thing is that recently I have had a medical examination about my ears as I’ve lost a lot of trebles and I can’t hear more than 10,000 Hz, which is very weird.

NG: I think we got used to touring naturally and we were excited to discover that life. It was pretty chaotic. It was well organised but it was new for us. We had no experience. We travelled all over the world, and it was a big disaster in our personal lives. We were touring with Sebastian Tellier, and there a lot of things going on. It was a nice experience.

Maybe this is the right album to have a second chance. Moon Safari doesn’t need one.

JB: It’s amazing because when we recorded this album there were several layers of sound that we imagined, like the orchestra, the electronic instruments… and with the new technology it’s really easy to listen to and hear all of this stuff together and make some movement and space in the sound. There are a lot of instruments and things playing together on so many tracks. The fact that everything is separated by space makes an interesting unique thing. I am so happy with the new ATMOS mix.

I really think that with this technology you can finally hear the real 10 000 Hz album that we wanted.

10 000 Hz Legend (20th Anniversary Edition) is out now on Parlophone. Shindig! #123 is in shops on 6th January and available to order here