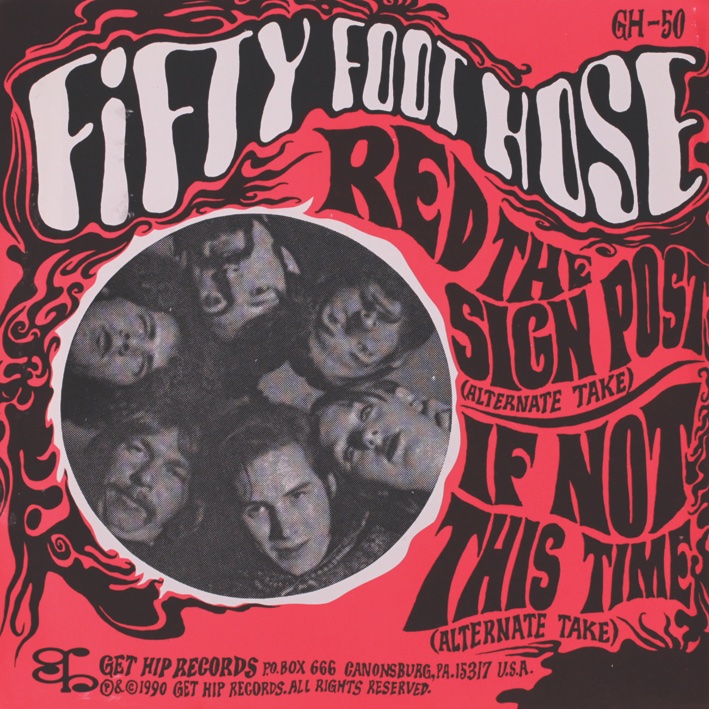

Fifty Foot Hose – If Not This Time

FIFTY FOOT HOSE’s astonishing 1968 album Cauldron united Californian folk-rock with bespoke electronic sounds. Overlooked in its day, it has gone on to become a treasured artefact among fans of avant-garde pop and dreamy psychedelia. Head gardener Cork Marcheschi speaks to RICHARD TURNER on the eve of both a new Hose studio album and a documentary about the band

Fifty Foot Hose belong to a rare, if not unique breed in the annals of rock history. Although their lone cult classic album, Cauldron, has a distinct mid-to late ’60s San Franciscan flavour, its use of electronics as the skeleton on which the flesh is hung marks it out as both ahead and out of its time. Even today, electronics in rock are used mostly as another colour in the palette, whereas for the Hose, “the levels were set around the electronics”. Bands and artists continue to be in awe of Cauldron – it’s still a beacon – an alternative road less travelled that has not been ruined by being copied to death, and is original enough not to sound too time-locked. It continues to appeal to a wide variety of artists, often those that themselves defy easy categorisation. The likes of Broadcast, Pere Ubu, Throbbing Gristle, Chrome, John Spencer’s Blues Explosion, DJ Vadim, Skinny Puppy, Hawkwind, and possibly even Deep Purple owe a debt to the Hose’s prescient avant-rock, whether by taking cues from them or directly sampling them.

No one would argue that Fifty Foot Hose were the only ones to focus on electronics in late ’60s rock and pop. The Silver Apples shared some similarities due to Simeon’s home made assembly of oscillators and foot pedals. Of all their contemporaries, The United States Of America perhaps come closest to the Fifty Foot Hose model in combining driving psychedelic rock, an appreciation of various American musical forms, striking female vocals and upfront electronic sounds, though each with their own distinct characteristics. In all three cases, electronics are the key to the music, rather than merely a texture within it. Incidentally, these pioneers were working independently of one another, Fifty Foot Hose only heard The Silver Apples and The United States Of America “years later”.

When Shindig! finally caught up with Hose mainstay Cork Marcheschi, it was apparently “perfect timing”, as a house move has meant Cork has been unearthing things that haven’t been seen in years, and his mind has returned to his past endeavours as a result of finding all kinds of reminders of his “art life, music life” including old acetates and even his own kind of notation for an electronic score.

Cork remembers getting turned on to music by “a very hip babysitter” and he was soon listening to blues, R&B, gospel and rock ’n’ roll. Later, at high school, he was keen to get involved in music-making whatever it entailed. “Bands showed up that might need someone to shake a tambourine and I was always game.” He subsequently became a bass player in a band playing the hits and standards of the day.

However, a pivotal event happened in 1962, Cork’s senior year at high school, as he explains. “I was at my friend Jeannie Gordon’s home and she put on Edgar Varese’s ’58 composition, ‘Poeme Electronique’. He wrote it for The Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World Fair. The building was designed by Le Corbusier and it had 200 speakers in the walls. You experienced the composition as you walked through this unique space. Hearing that piece of music changed my life.” At that moment, the idea of electronics and avant-garde music collided, though it was yet to manifest itself in Marcheschi’s music.

For the most part of the ’60s, he was a jobbing musician at a time when opportunities were ample. Cork revelled in the nurturing atmosphere of The Bay Area before San Francisco became the hip place to go. “In ’65, ’66 and the start of ’67, the SF Bay Area was as fertile as the gold fields were, until all of the outsiders came in and brought their uncoolness with them. Before The Summer Of Love, the city was full of young and old from every place and every colour. Until early ’67 this was a haven for music of all types – there were hundreds of places to play and there were people who go and see stuff – a unique moment in time.”

Fifty Foot Hose evolved from a band called The Ethix, who were a mainstay of the “San Francisco peninsula scene in ’65 and ’66”. The Ethix had a regular gig in San Mateo. “Over the year that we played there, Wayne The Harp (from AUM) was our guitar player. When he left we got Reese Sheets who went into The Vejtables. Jan Errico, the singer with The Vejtables was in classes with me at The College Of San Mateo. Pete Albin from Big Brother was in my volleyball class. The Beau Brummels were at The Morocco Room in San Mateo and The Warlocks (later The Grateful Dead) played in San Carlos at The Chalet.” It was a very happening scene. The Ethix even opened up for Buck Owens & The Buckaroos and Eartha Kitt at a New Year’s Day ’66 performance at San Quentin Prison!

Despite a later line-up of The Ethix releasing the mind-bogglingly un-commercial experimental single, ‘Bad Trip’, Marcheschi created a new name for a more adventurous venture. At the core of this new group were Cork and David Blossom. “David worked at Draper’s music store in Palo Alto. He taught guitar and worked the counter. He played folk stuff and contemporary pop stuff. He learned a lot of songs by the records his students would bring in to teach them. Dave was familiar with jazz, folk and modern classical. I introduced Dave to Luigi Russolo and his Futurist Noise instruments from 1912. Dadaism was a huge influence, [as were] John Cage’s ideas about indeterminacy.”

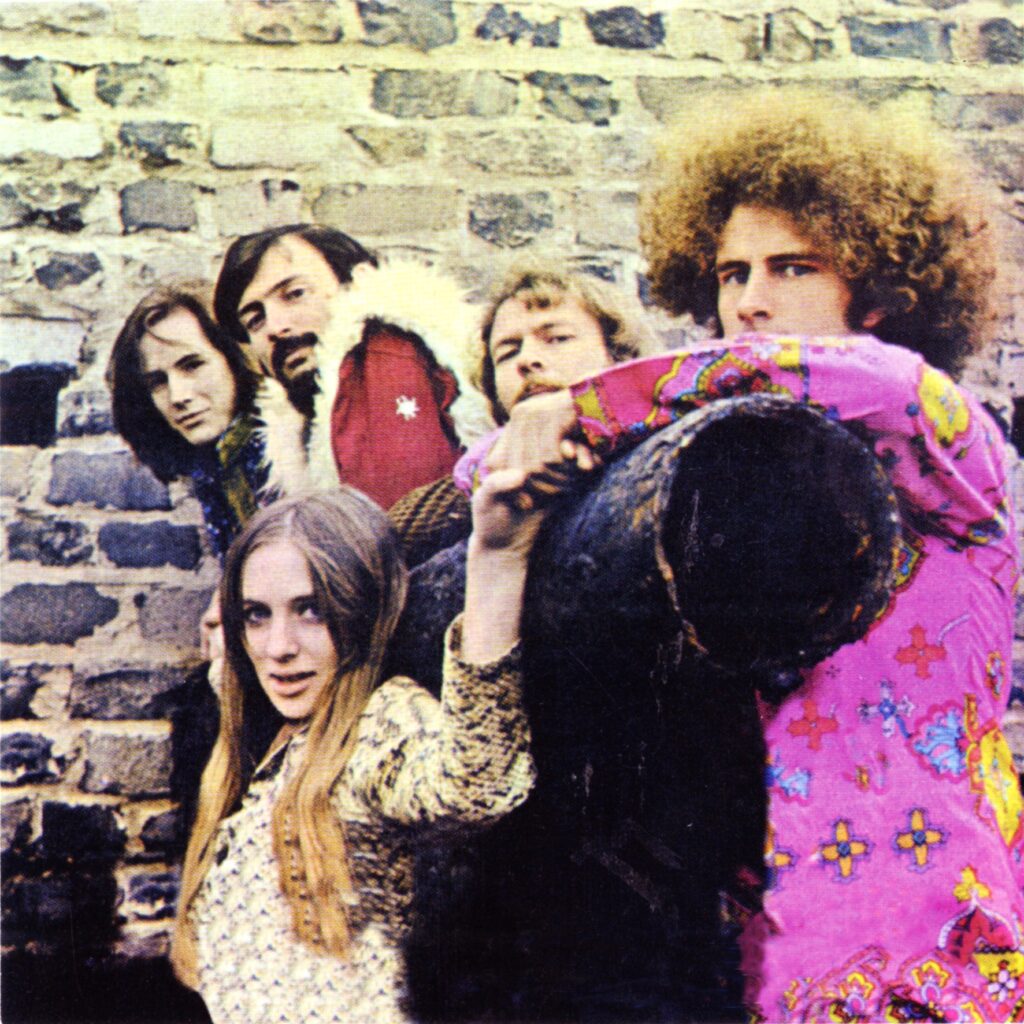

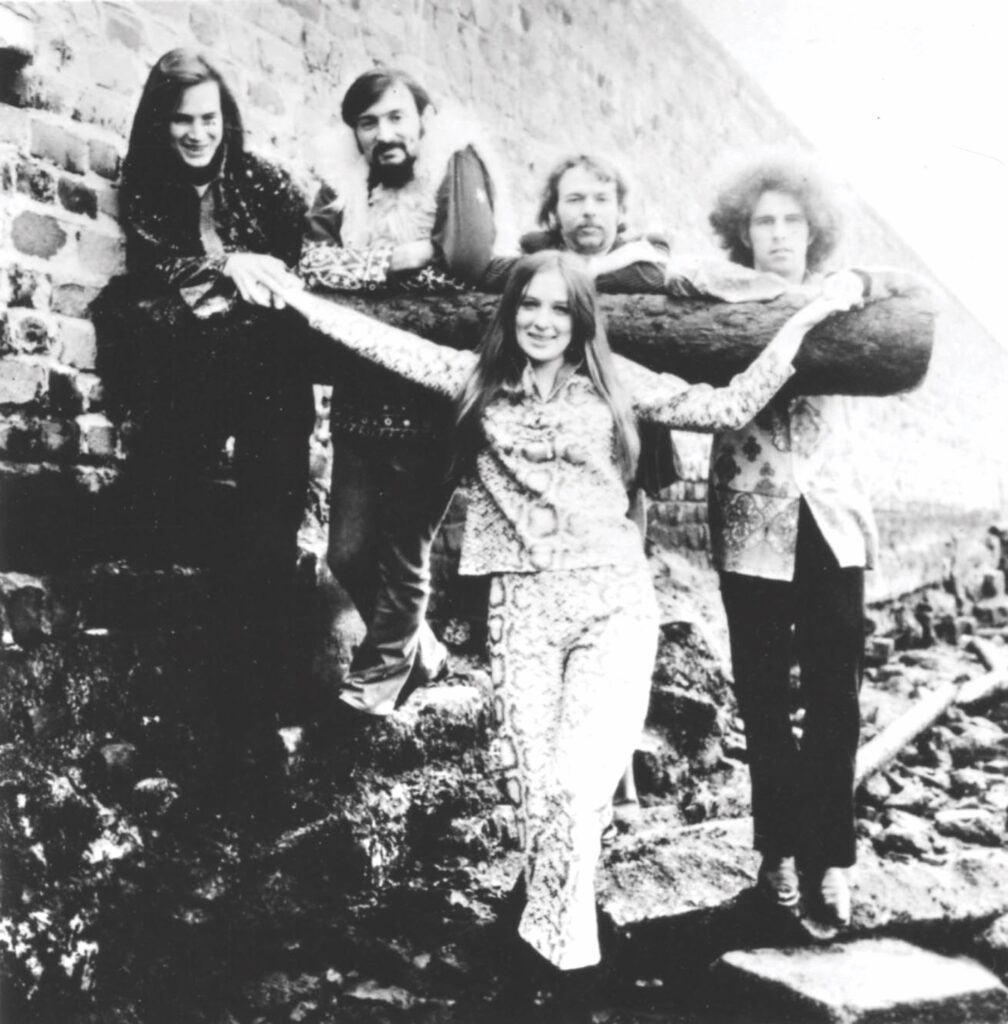

That versatility and open-mindedness provided the perfect foil for Marcheschi. “David was a gifted player. He had a great ear, could write, improvise smart (not just bunch of notes) and was fearless.” Singer Nancy Blossom “was David’s wife and was not afraid of any thing we did. She was so natural that I never thought about what we asked of her until 20 years later. Nancy just loved to sing and was never a diva about it.” On percussion, “Kim Kimsey was a seasoned drummer of many rock bands. After the Hose broke up he worked with The Pointer Sisters, went to LA and did some session work and toured with Gary Lewis & The Playboys.” Bringing perhaps a more straight forward, contemporary aspect to the group was guitarist Larry Evans, who also wrote the catchy ‘The Things That Concern You.’ Cork explains that “David and I needed a rhythm guitarist so we could get some work and earn money while we developed the Hose and Larry happened by at the correct time. But he wasn’t a team player. He took enough drugs to make up for those of us that didn’t take any.” In fact, whilst much of the album sounds almost dementedly psychedelic, apparently, only one member actually took drugs. “Larry took everything all the time. Larry is now dead.”

After giving up the bass in order to make way for his electronic endeavours, Cork assembled an eclectic mix of gear which consisted of “a Klemt Echolette – three tone generators fed into each other controlled by a volume pedal, a Yoy Yoy Bow Wow, an Electro-Voice microphone with an on and off switch – very important. This was used for controlled feedback. You hear it in ‘Fantasy’ and ‘Red The Sign Post’. The feedback worked best with a Fender Dual Showman Amp.”

Like many budding electronics enthusiasts, surplus WWII gear proved useful, as Cork employed a “12-inch plastic Klaxon speaker with a 10-pound magnet and heavy plastic cone. It was used on battle ships and it had to be loud enough to be heard over war. I had this mounted vertically and ran low frequencies through it. The cone would be full of half-inch steel ball bearings that would rumble and dance. I wish I could find one of those now. Squeaky box was a little keyboard-like thing that played high-pitched single tones.” In addition to this battle-ready gear, “there was an electric siren – a 12-foot long carpet tube that was connected to a contact mic. I beat it with sticks – rolled big marbles through it. And two Theremins.”

In addition to the more regular band opportunities in the area, there was also plenty going on in the world of art, sound design and sound technology. Members of Fifty Foot Hose made the most of their opportunities. “I was a member of EAT – Experiments In Art And Technology. They had a meeting at the AMPEX headquarters and Tony Nazzo from The Tape Music Center was there. He gave us the run down on the place and invited anyone interested to come to one of there evening sessions. David (Blossom) and I went and it was great. These were people who had years of experience in the new music field and were welcoming of two kids from an experimental rock band.”

https://youtu.be/AzAzJUOpT5w

At the time, electronics pioneer Don Buchla was just developing his keyboard-less synthesisers and the first of them were at The Mills Tape Center. Fifty Foot Hose were at a pretty unique time and place. “We learned to use a Series 1000 Buchla. We saw other people perform new works and I was invited to perform solo with other solo electronic people in the rotunda of The Museum Of Modern Art in San Francisco. Four to six electronic musicians were set up in a circle in the middle of the rotunda and we took turns playing and shifted every 15 minutes. It was great – this was part of The Machine Show that had travelled from MOMA in New York.”

Whilst Cork enjoyed seeing some of the rock bands around (“The Electric Flag, Hendrix, Cream, Mother Earth, Lamb”), he felt that Fifty Foot Hose had more in common with “fine art performance groups like the Guttai and Fluxus”. Despite this, and the electronic aspects of the Hose, there is an undeniable psychedelic rock aspect to the music. The heavy riff-age on ‘Red The Sign Post’ rocks as much as anything can, and according to Hose fan Julian Cope, could well be the inspiration behind Deep Purple’s ‘Space Truckin’’ from ’72’s Machine Head. Whilst not talking specifically about this example, Cork suggests it wouldn’t be a one-off. “We have been ripped off a lot. In a few cases it has been a total theft of an entire composition minus the vocals.”

When they played with Love at The Fillmore, Fifty Foot Hose really moved the crowd with its rumbling deep bass oscillations. Due to the venue’s “second floor wooden structure, you could really get the building resonating.” Cork reminds us that San Francisco is “earthquake country”, so the vibrations were so deep that they probably terrified the audience into thinking something huge was happening! Using two oscillators, Cork was able to “bring them apart slightly and get those beat tones” resulting in a sound that felt “like some impossibly large machine”. These sounds, combined with the lighting and atmosphere of the gig would, Cork suggests, appeal to the audiences “pre-linguistic feelings” and “pre-cognitive relationship” to dark and light. One can only assume that people were freaked out.

Despite playing rock venues like the Fillmore, the band “were not received well – the music didn’t fit with the established hip, cool, groovy, pop and psych music of the moment”. There was small and loyal group of fans. “A hardcore following and they kept us going.” Live, the band was prone to doing experimental, avant-garde type of acts within the set, more akin to performance art than acid-rock. “In the middle of a song every thing would cleanly stop and rice would be rained onto the miked cymbals. We used a dark room timer that would start a break in a song and for the next 60 seconds any body could do whatever they wanted as long as they were back in when 60 seconds were over.” This may have simply confused audiences that had become used to 10-minute guitar solos. Cork and company were just “trying to make new music.” Rather than deliberately trying to antagonise their audiences, Fifty Foot Hose’s intention was “to engage, entertain… and bridge art and musical experiences”. Cork continues. “David and I were young – in love with our idea and blind to reality. If we weren’t we would never have tried. We would have liked to been adored.”

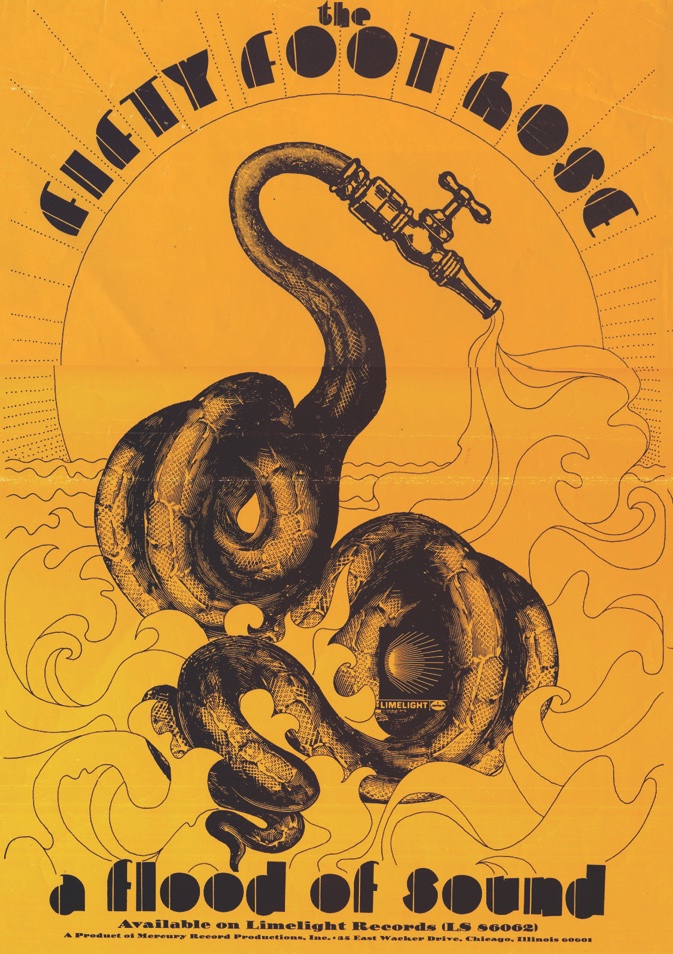

Having got their project together, the Hose needed a label to put out an album. Cork managed to get an appointment with a music business lawyer, left him with a demo tape, and waited. Six weeks later, there was a call. “Robin McBride from Mercury Records’ new label, Limelight. Robin liked the tape and wanted to hear the band the next day. Robin came down, loved the band and signed us on the spot. We were treated well by Mercury.”

Many bands at the time struggled to capture their sound with sometimes rigid recording engineers, or tight label restrictions, but not so the Hose. They got the man that had worked for The Charlatans (including capturing that electric autoharp!) and who went on to be the soundman extraordinaire for The Grateful Dead. As Cork elucidates, “We were very lucky to have Dan Healy as an engineer/producer. We provided him with challenges that he found fun and interesting. So when we got to Trident Studios for sweetening and mix-down, David and I felt like we could try anything and Dan felt free to toss in his ideas as well. We never fought or argued. The music had a life of its own and we got out of the way and let it take us places.”

Cauldron received “the standard support from Mercury – press release, promo pictures, poster articles in teen ’zines written off the press release”. They also got “late night airplay and more work as Fifty Foot Hose – not a covers band trying to make money. The deejays who liked us really liked us and had on-air interviews”. Despite this, the album never really caught on at the time. “The good and great reviews didn’t come till the late ’80s.” In retrospect, we can answer Ralph J Gleason’s “I don’t know if they’re premature or immature?” with the former.

Nineteen-Sixty-Eight was a tumultuous year. The supposed Summer Of Love had been swiftly followed by riots, conflict and increasing opposition to the war in Vietnam. Fifty Foot Hose responded accordingly. “‘Red The Sign Post’ is an anti-war statement,” acknowledges Cork. The song is sung by Nancy Blossom with a kind of punk-rock ferocity not dissimilar to Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, totally unlike any other singer at the time. According to Cork, this song “requires the vocalist to be at war with war and attack the song. There was no coaching – she was ferocious”. When the song was played live, it was apparently “like standing in front of a run away train”.

In stark contrast to this song, there’s a mellow and almost straight version of a Billie Holiday classic. As Cork recalls, “David had his guitar and was just playing some chords and Nancy started to sing ‘God Bless The Child’. We thought it might be fun to see if we could bring the electronics into a jazz standard.” Whilst the guitar and voice are fairly faithful, Cork playfully adds some electronic treatments, un-standardising it. Given the rest of the material on the album, it’s perhaps unsurprising that “the record people asked for this song to be on the album. They were hoping for some airplay”.

“Cauldron is our version of a tone poem. It started with a vision of Macbeth and the witches’ cauldron and it went from there. The language in Cauldron speaks abstractly and metaphorically to the lies that that the government told us. The Chicago Seven, Agent Orange, Kent State, moving into Laos. It was all too much and it was all on TV. ‘If Not This Time’ was a lyrical homage by a couple of young musicians to Arnold Schoenberg. I know how pompous that must sound but we were earnest in our work.” Not long after the Cauldron was released, the band dissolved due to members joining the cast of Hair in order to survive financially.

Despite having an enormously varied and successful life as a teacher, artist and sculptor, Cork Marcheschi is rightly proud of Cauldron. “It’s great to be recognised by other musicians and critics. It’s a great compliment when someone states that they have listened and appreciated. We never got much else – so credit is huge.” But the Hose are alive and well today.

With Cork Marcheschi the only original surviving member from its first incarnation, the current version of Fifty Foot Hose have been together for over 20 years. “People started calling me in ’86. ‘Are you Cork Marcheschi from Fifty Foot Hose?’ Several of these people had fanzines and started to write articles. In ’93 I re-released Cauldron on my own label. It was instantly picked up by distributors around the country and it got great reviews. I was shocked, pleased and having fun. In ’94 the owner of Aquarius Records asked if I had the band together because she would like to have us play a show.” A new band was assembled and has stayed together ever since. Full of enthusiasm, Cork claims the current line-up are “fearless” and “having more fun now than ever” with the group dynamics perfectly balanced and inhibitions virtually non-existent. “We don’t care… we can’t make mistakes, each time we get together, we’re freer.”

Fifty Foot Hose played at The Other Minds Festival in San Francisco not so long ago, featuring “bands that don’t have a category” – a perfect fit for the Hose who continue “making music somehow they can’t shake.” A new studio album and a documentary are due 2016.

Cauldron is out now on Big Beat

With special thanks to Cork Marcheschi and Walter Funk III.

Extracted from the article in issue #55. Order now to read the full feature.

Subscribe to Shindig! here to read many more articles like this in our 100 page monthly print magazine