The Last Movie: Counter-Cultural musings from TSPTR. Dossier #9

In the ninth of our monthly counter-cultural musings from TSPTR, Dennis Hopper’s dreaming in America

At the tail end of the ’60s Dennis Hopper had it all. Actor, director, artist and provocateur. He’d earned his acting stripes from his earliest appearances alongside the likes of Jimmy Dean, starring as a troubled teen in Rebel Without A Cause and had struck up friendships many of the fine art world’s hippest and best including Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol. He’d go on to write, direct and star in the film that became a totem for the counterculture – Easy Rider. So, when it came to his next directorial outing post Easy Rider (a bona fide blockbuster, offering an enormous return on a not too hefty investment) the studio handed Hopper a blank cheque and free rein.

This next excursion would be a bizarre one, a 1971 passion project named The Last Movie – an anti-imperialist drama about a stunt coordinator who attempts to stop actors on the set of a Peruvian Western from killing each other for the camera. The film bombed, mainly due to its ridiculously high concept meditation on cinematic storylines. It was critically praised yet financially disastrous, a toxic combination that set back Hopper’s Hollywood career for well over a decade.

During the editing and post production of The Last Movie, photojournalist Lawrence Schiller and actor-screenwriter L.M. Kit Carson made a film about Hopper’s creative process. The directors followed Hopper around Los Angeles and Taos, New Mexico, and ended up with 1971’s The American Dreamer, a quasi-documentary and masterclass in meta movie making.

Schiller’s concept was “to do a story about an actor who had submerged himself into his own myth”. He originally wanted to focus on Paul Newman, whom he’d worked with while producing a photo sequence for Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid. Newman declined so Carson suggested Hopper, stating “Why don’t we go out and meet Dennis Hopper because he’s actually living the life of his character in Easy Rider, he can’t escape it.” It was then that Schiller realised he would be “making a documentary about an actor playing an actor in a movie”.

The American Dreamer presented a startling, candid portrait of a unique personality intersecting with a critical moment in cultural history: New Hollywood. It is not, however, a documentary – Schiller recently stated that although the style pays homage to the genre – especially the 1922 staged silent documentary Nanook Of The North – Hopper was always performing. “An actor playing an actor.” According to the director, there isn’t a moment in the film when his subject doesn’t understand he’s being filmed: In fact, Hopper is even credited onscreen as a co-writer.

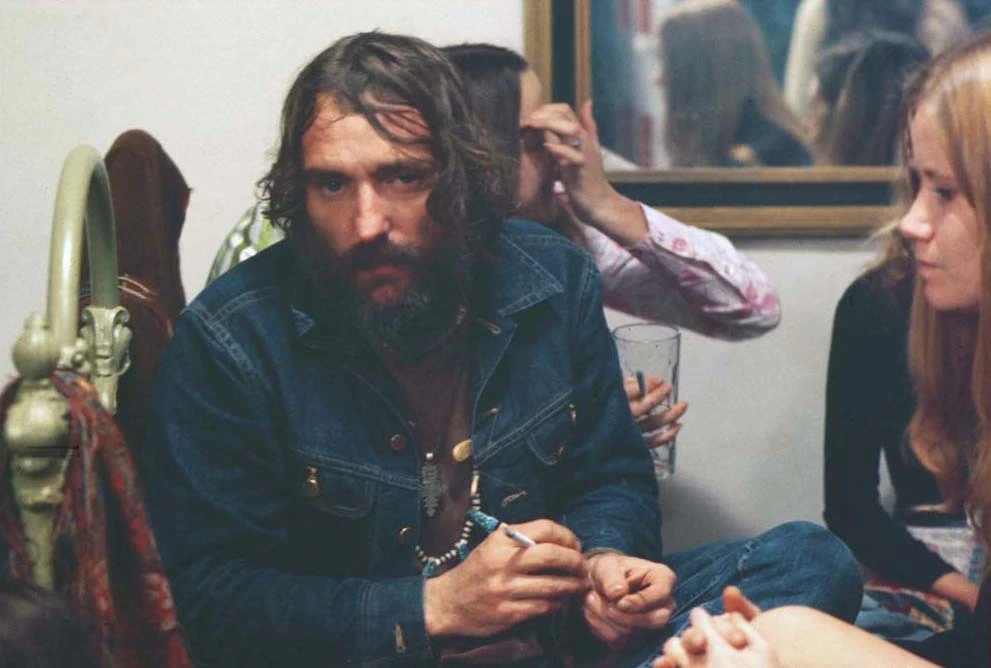

That said, much of what we get is pure Hopper or possibly Hopper playing Hopper. He’d just come out of his disastrous eight-day marriage to The Mama’s And The Papa’s Michelle Phillips and was seemingly looking to sleep with every woman he could. Meanwhile, in reality, his appetite for booze and drugs was tipping into addiction. More than filming him working on The Last Movie, Carson and Schiller film Hopper not working on it: he’s firing rifles in the desert; he’s offering philosophical pearls such as, “I don’t believe in reading”; he’s baring his ass for a harem of 30 naked young women in a group “sensitivity encounter”.

The main narrative, according to Schiller, “was Hopper’s transition from first-time director to serious director. And my transition from a magazine still photographer to a movie director.” The period-specific film also unintentionally presaged Hopper’s future as an artist: In the film he conspicuously references Orson Welles’ late-career Hollywood travails, in part predicting his own failure. Alongside Orson Welles, the other phantom on Hopper’s mind is Charles Manson, whom he admits having recently visited in jail. At points, filling his compound with stoned chicks and lecturing them, it seems like Hopper, having already grown the beard, is considering picking up where Manson left off.

A few years ago, Schiller, also known for his intimate photo shoots of Marilyn Monroe, donated The American Dreamer to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, MN and gave the institute unlimited rights to exhibit the film for further film-restoration fundraising. Though The American Dreamer has become a textbook example of how a documentary’s aura can propagate both myth and anti-myth, its viewings had previously been restricted to student audiences only. Hopper originally mandated that the film could only be shown on college campuses.

The final cut of The American Dreamer represents a highly constructed group effort that pushes the limits of documentary. In one portion of the film, Hopper – a great contemporaneous speaker – confronts Schiller about his invasive techniques. The scene was apparently contrived by the filmmakers to achieve narrative tension. The mildly raunchy sex scenes were also deliberately staged.

Nonetheless, Schiller says he approached making the film “like a sponge”, soaking up and preserving as much as he could from his on-the-ground, 30-day shoot with Hopper. One lesson he claims to have learned was the importance of collaboration, in this case with Kit Carson: “We were different sides of the [same] coin,” Schiller recalled. “Kit is an intellectua … He was deep into the meaning of the scenes. I was interested in the body language.” He also singles out Nick Venet, the composer responsible for the impressive soundtrack.

It’s clear throughout American Dreamer, however, that Hopper never learned to collaborate. All the way through, the film rides on his appeal as a performative genius who’s both a control freak and someone who suffers deeply from feeling alone