Shindig! Issue #158 – If You’re Feeling Sinister

Here at Shindig! Towers, December is far more about ghosts and bleak ’70s TV shows than it is John Lewis adverts.

HUW THOMAS chats with British Film Foundation curator VIC PRATT about wicked witches, eccentric professors and replanting old roots all in the name of seasonal fun

It’s long been tradition to swap ghost stories in the bleak midwinter. In the 1800s, Christmas ghost stories were publishing dynamite, haunting the pages of even the most sober periodicals. In the early 1900s, Cambridge scholar MR James was reading his bespoke tales of terror to friends and students. By the ’70s, Christmas terrified one Vic Pratt, today the DVD and Blu-ray producer for the BFI. “I was spooked out at the age of six by The Wizard Of Oz on Christmas Day, on every year without fail,” he tells Shindig! “Not long after that, my dad took me to Hounslow West Odeon to see Snow White & The Seven Dwarfs and I was utterly freaked out by the sight of sobbing dwarves paying their respects to Snow White in her glass coffin. Great memories!” Pratt has worked at the BFI since ’98 and has been instrumental in popularising many film and television productions popularly associated with folk-horror, the strain of fiction informed by folklore and superstition that’s become a phenomenon over the last 15 years. That’s if you believe it exists at all.

For those unfamiliar, folk-horror is the freakbeat of film. A retroactive sensation. Nobody knew they were making it at the time, but fans just know it when they see it. Vic Pratt is reticent to define it. “To name it is to know it and to know it is to lose it,” he explains. “Before you can even begin, you have to work out what you mean by folk and what you mean by horror. As (The Wicker Man director) Robin Hardy once said to me, ‘You pays your money, you takes your choice.’ I will say that the genre – if it is a genre – can often be seen to revolve around some basic conflicts: town versus country, old versus new, god versus gods, them versus us, urban education versus country cunning. The creeping onset of the pavement over the fields.”

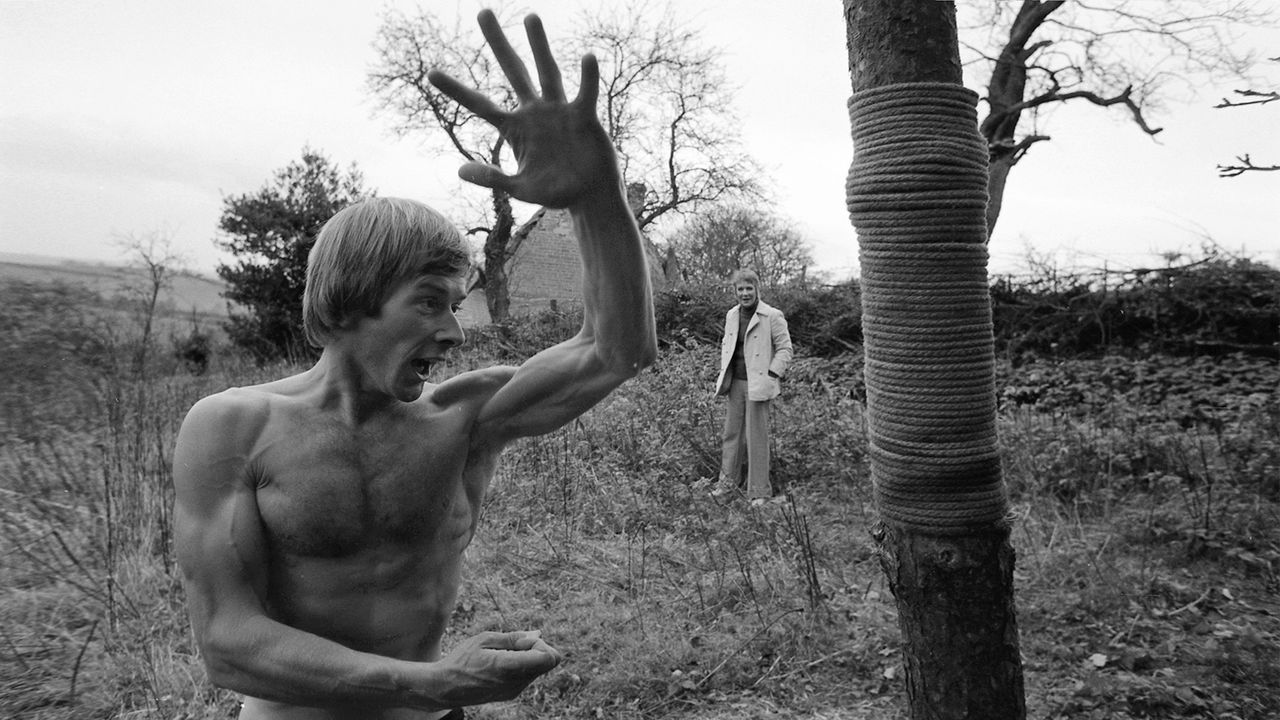

Pratt, with William Fowler, founded Flipside in 2006, a program at BFI Southbank that puts forgotten, unusual films under the spotlight. One night in 2008 may have helped spark the folk-horror boom. “We showed a brilliant Play For Today by John Bowen called Robin Redbreast, about a young woman who becomes trapped in a remote rustic community, alongside an equally fabulous Nigel Kneale drama called Murrain, about an old woman who is accused of witchcraft,” Pratt recalls. “No-one had decided it was called ‘folk-horror’ then, so we called our show ‘The Sinister Folk’.” Pratt considers Robin Redbreast, first shown in ’70, “a key work in the canon… [sharing] umpteen ideological points of contact with The Wicker Man”.

The BBC’s A Ghost Story For Christmas series is another key work, one that grows in stature every winter. A run of yuletide spinechillers that originally aired between ’71 and ’78, it produced slow-burn horror classics in its adaptations of MR James’ A Warning To The Curious and Charles Dickens’ The Signalman. For Pratt, the Ghost Story series represents a purple patch in British television. “Nostalgia’s not what it used to be and will only go a short distance towards explaining the perennial appeal of these programmes,” he argues. “I’d say that this was a golden era for small-screen drama, with immensely talented writers, production teams and performers. Programme-makers had the opportunity to take risks with their work which might be considered too economically or ideologically or intellectually uncertain to take today. It was almost a pre-requisite to try and challenge your audience, to unsettle them.”

Whistle And I’ll Come To You, produced for Omnibus in ’68 but usually considered the starter pistol for the Ghost Storyseries, is a James tale of an academic whose philosophy is shaken by a series of unexplained phenomena on the East Anglian coast. It was directed by Jonathan Miller, whose earlier Alice In Wonderland had been an exposé of the tedium of adulthood just as British pop turned to childhood whimsy. Here, he transforms a story he considered “rather a mandarin, Cambridge don’s piece” into something more oblique and distant. The academic Professor Parkin is played by Michael Horden as an eccentric old fusspot so bumbling he verges on unintelligible, and Miller’s wide-angled direction puts a proscenium between the protagonist and the viewer. A huge part of the eeriness of Whistle lies in its simplicity. “When I watch these old programmes now, the absence of glossy big-budget effects and fancy-pants CGI doesn’t dismay me – it delights me,” enthuses Pratt. “It seems thoroughly refreshing, in fact. You need to use your imagination. Splendid brain-food!”

When the Ghost Story series came to an end, its place in the ’79 BBC Christmas schedule was taken by Schalcken The Painter, a gothic horror disguised as a docudrama in which the real-life Dutch artist is played by Jeremy Clyde of Chad & Jeremy fame. Few kids would’ve been allowed to stay up for that, but the ghouls were still out of get them at the Saturday pictures; Pratt points to The Man From Nowhere (’75) and Haunters Of The Deep (’84) as eerie highlights in the Children’s Film Foundation catalogue. For contemporary filmmakers influenced by folk-horror, the conventions of vintage film and television seem to be as influential as the stories. Starve Acre, Daniel Kokotajlo’s new film about a couple whose rural idyll is disrupted by grief, replants old roots. It was shot with ’70s lenses and is scrumptiously lit. Matt Smith’s Richard is a ruffled academic in the MR James tradition, while Morfydd Clark’s Juliette is reminiscent of Norah Palmer from Robin Redbreast. “I’m really delighted that a whole new generation of folk-horror fans seems to be emerging and thriving,” says Pratt. “Kids who grew up watching The Owl Service or Moondial or The Children Of Green Knowe are writing about the subject or making folk-horror films of their own.” Sinister folk, you know what to watch this Christmas.

Robin Redbreast, Ghost Stories For Christmas Volumes 1 & 2, Schalcken The Painter, The Children’s Film Foundation Collectionand Starve Acre are available now from bfi.org.uk

Order issue #158 here