Issue #159 – Tom Wilson

Unheeded in the archives of ’60s popular culture, TOM WILSON was the producer behind the era’s most daring artists, and the best-known overdubbing session of all time.

But behind his lightning-in-a-bottle work with Dylan, Zappa, Simon & Garfunkel and The Velvet Underground lies a treasure trove of delights from Burt ‘Robin’ Ward to Soft Machine.

In this article extract, SEÀN CASEY sets the scene

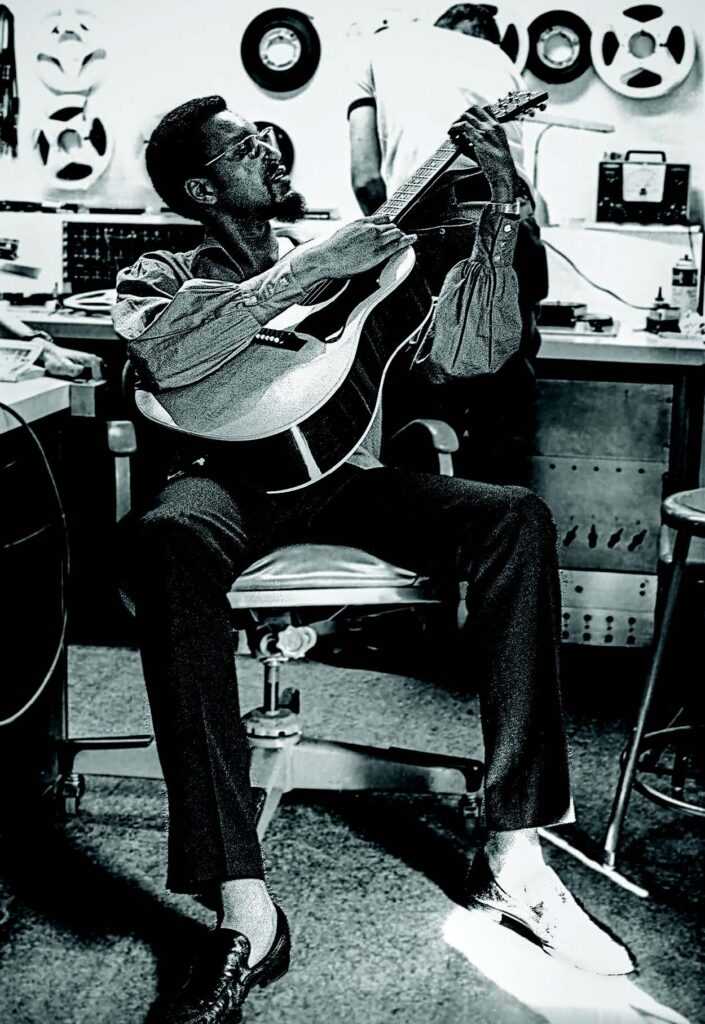

A Texas native, Wilson was imposing in stature (six-foot four), urbane in character. His career began at Harvard University. “I was president of the jazz society there and began to meet some of the musicians. We sponsored one of Dave Brubeck’s earliest concerts. I did interviews with Charlie Parker and others, and we recorded Herb Pomeroy, Serge Chaloff and some more. We started to can programmes, and that’s where I learned radio and recording technique.”

After graduating, he launched Transition Records, a jazz label that became home to artists including Sun Ra and Donald Byrd. When it folded in 1957, he moved to United Artists and then Savoy, before joining Columbia as an in-house producer where he was assigned to folk revival poster boy Bob Dylan. “I’d been recording Sun Ra and Coltrane, and I thought folk music was for the dumb guys,” Wilson said. “This guy played like the dumb guys. But then these words came out. I was flabbergasted. I said to Albert Grossman, who was there in the studio, ‘If you put some background to this you might have a white Ray Charles with a message.’”

The pair used the studio like a lab: trying and testing new combinations of players and sounds. Tuned into the emerging folk-rock wave, for Bringing It All Back Home, Wilson began overdubbing instruments – applying his cookie-cutter to recordings for Dion’s Wonder Where I’m Bound, which remained unreleased until ’69. “He didn’t divert what you were doing. He just kind of directed you,” Dion wrote.

Wilson’s work with Dylan ended in disagreement, supposedly over the final mix of ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, with the artist sardonically suggesting he would ask Spector to oversee his next album. Wilson shrugged it off, moving to MGM where he recruited musicians from Columbia, including Al Kooper, who famously joined that session. “He really saved my life that day on that ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session,” Kooper remembered. “I went over to Tom Wilson, and I was invited just to watch, you know, and I said, ‘Man, why don’t you let me play the organ? I got a great part for this.’ Which was bullshit. I had nothing. And he said, ‘You’re not an organ player’. And then they came to him and said, ‘Phone call for you Tom.’ And he just went and got the phone. And I went into the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. He just said I wasn’t an organ player.”

At MGM, Wilson was top dog, broadening the Verve imprint’s output which sat firmly in folk until then. He embodied its rebrand from Folkways to Forecast, whipping out varied output, often without consulting anyone. “It took three days to cut an album. Then we never heard it again until we saw it in the stores,” Kooper said.

To read the full article order Shindig! issue #159 here