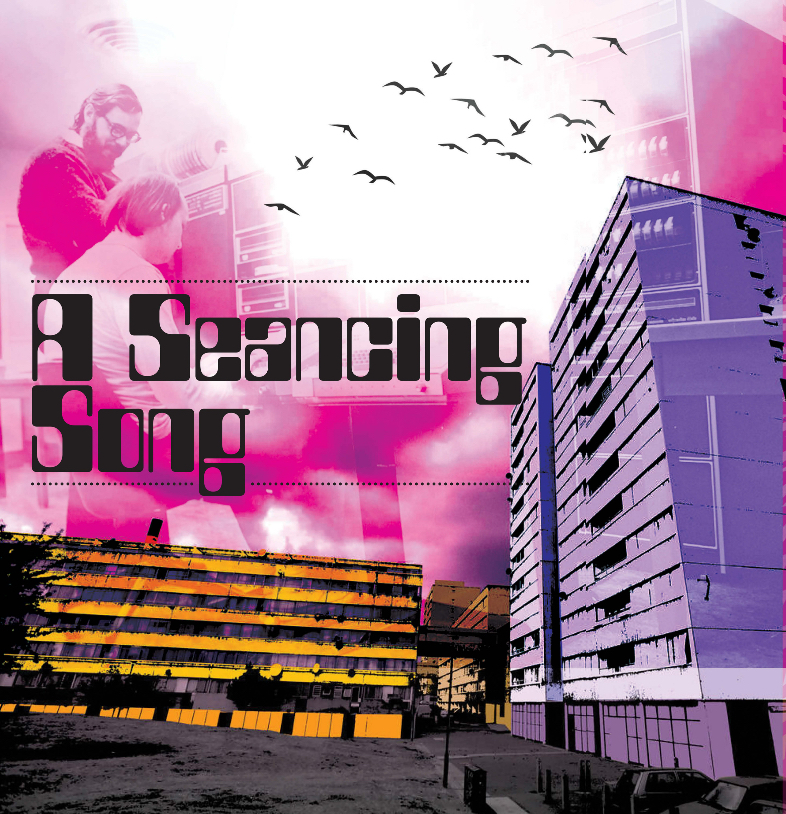

Issue 160 – Hauntology

Nebulous and indefinable by its very nature, the notion of HAUNTOLOGY has nevertheless stuck its shadowy fingers into the nooks and crannies of 21st century popular culture.

Whether it’s the hankering for a halfremembered, half-imagined past by a Gen X hitting middle age and choosing forest walks and arcane folklore over fingertip technology and hyper-consumerism, or a broader sense of nostalgia and cultural memory being lost as the old and the new become increasingly intertwined, there’s been something in the air since the turn of the millennium.

CAMILLA AISA enters her own Ghost World, with the help of key voices from music, literature and beyond.

In this extract she muses “What exactly is Hauntology?”

From the first instances of the “hauntology” moniker being used, the artists to which it was applied were noticeably diverse. There was, for instance, the avant-pop of Broadcast, the fractured soundscapes of Burial and the voracious electronic collages of The Focus Group. The principal trope uniting them all could be traced back to their discursive relationship with the past, and the consequent unveiling of a new, productive take on nostalgia. The particular nostalgia expressed by hauntology isn’t merely a longing for an actual past but, rather, for past visions of the future. In the genre’s decades of reference, imagining the future indeed had its share of eeriness (something hauntology releases, with their penchant for the occult, would eagerly highlight), but there was also a sense of hopefulness to it. The evolution of technology was slower, leaving time to wander and to wonder, much to fantasise about. The mystery of it all was beguiling. From this perspective, hauntology can be seen as the manifestation of a need to claim a future that could be dreamed about, and to maintain contact with the past that dreamed it. “Haunting,” Mark Fisher wrote, “can be construed as a failed mourning. It is about refusing to give up the ghost or – and this can sometimes amount to the same thing – the refusal of the ghost to give up on us. The spectre will not allow us to settle for the mediocre satisfactions one can glean in a world governed by capitalist realism.”

Also acting as a common thread among the diverse musics making up hauntology is a deep well of cultural references. Hauntological music wears its loves and obsessions on its sleeve, and those loves to define, hauntology music is instantly recognisable for its crackles, hisses and glitches. “Crackle makes us aware that we are listening to a time that is out of joint,” Mark Fisher pointed out. “It won’t allow us to fall into the illusion of presence.” In this respect, hauntology is not unlike a Bertolt Brecht spectator, conscious at all times that what they’re experiencing is not reality itself but a representation of it.

Buy issue #160 here to read the full article