Bill Fay – Planting Myself In The Garden (2012 interview)

With a rabid cult reputation and fearsome outsider status that stems from a triad of early ’70s albums and a collection of his ’60s demos, BILL FAY’s name continues to engender a rare reverence and hushed tones among connoisseurs of introspective, leftfield pop songcraft.

“It wasn’t me who left the music, it was the music business that left me.”

HUGH DELLAR meets the North London enigma

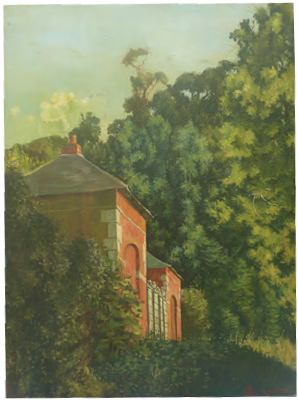

In my bedroom, I have hung a painting done by my father in 1971, two years after I was born. Entitled Instant Artificial Recollections Of Childhood, it’s a split canvas featuring two slightly different versions of what is essentially the same image – a woman (not one particular visually specific woman, but rather a symbolic representation of a woman) standing with her back to the viewer in a garden as squadrons of fighter planes fly high overhead. In the right-hand side of the painting, thewoman is further removed, the garden slightly elongated, the memory more distant and removed. More like that which lives in the mind, the real overlaid by the patina of memory and its many falsifications. Despite never having asked, I’ve always presumed the woman to be my nan, who died when I was 14 and of whom I have only fragmented memories, the scene to be the Croydon house my dad’s folks relocated to after Camberwell and the time the years of The Blitz.

I mention this because I suspect that one the main reasons why Bill Fay’s trajectory as what he terms “a song finder” resonates with me quite so deeply is because it echoes and mirrors much of what my father, now 83 and still painting every day of his life, has been through – and has passed down to me.

Much of the music Bill has gifted us that hits me hardest is that which generates instant artificial recollections of childhoods I may well have never actually had. I put on ‘Katie And Me’ and find my mind flooded with images of pebble beaches, sunburnt necks and popping blisters, the screech and caw of seagulls, brass bands on bandstands; ‘Sing Us One Of Your Songs, May’ conjures up the smoky south London pubs of my father’s early ’50s salad days, the piano singalongs echoing down foggy dusk streets, men with hat brims tugged down and collars pulled up and against the cold puffing on hand-rolled fags.

“As a teenager, I was once dragged by my dad into our garden and told to stare at a tree. “It’s a tree” I told him, in answer to his questions about what it was I was looking at, which caused him to splutter in incredulity and point out that the eyes he had given me were being wasted. “It’s not just any tree. It’s THIS tree. Full of tree-like qualities and yet only its own unique self.” He then went on to explain the problems of truly seeing things and then painting them when the mind collates every example of a thing that it encounters and from them forms an archetype – tree, say, or duck – and these interrupt the act of actually observing that which is before you.

This sense of being awake to what we encounter, to feeling and knowing its wonder and uniqueness, and of accessing the frames of mind that allow us to see things as they actually are – or at least as they can be – lies at the heart of Bill Fay’s music, music that somehow transforms such mundane and everyday objects as patches of parsley and factory floors, door keys and teddy bears by feeling in them a wider, clearer truth and meaning. Like an earlier London mystic, William Blake, Bill Fay leaves you feeling that it is still possible “to see a world in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower”, yet also insists we recognise the flipside and face down hell as it encroaches upon us. There is hope and the comforts of home, but also a harrowing sweep through the pain and injustice of the strange little planet we happen to find ourselves passing through.

Much like my father painting in the free time snatched amidst a life spent hustling for brass by running a bed & breakfast and selling antiques and old cars, Bill Fay has spent a working life also managing to craft and collect songs and the fact that he not only remains among us, but is still recording and perhaps only now finally finding the fame and fans he so richly deserves, is something we all should give thanks for. What follows is his story. Or part of it. Written in the knowledge that all views inevitably contain the viewers.

Born during the war, Bill Fay grew up in a tight North London community where music provided release and solace, laughter and relaxation. His mother’s side of the family was particularly musical, with her five brothers and sisters all able to play instruments by ear. The family would frequently have get-togethers on a Sunday that would cause passers-by to stop and listen a while. His father was also an adept guitarist and wrote and sang songs in the music hall tradition. As Bill himself puts it, “Although I was to grow up as part of a significantly different generation, I remained, and remain, deeply connected to that generation,” and it doesn’t take much to hear traces of earlier eras echoing through his recordings.

At some point during his youth, a piano arrived in the house. Bill remembers its appearance roughly coinciding with the purchase of a Dansette record playernand a guitar for his older brother, both of which led to rock ’n’ roll filtering through. After early experiments failed, Bill was initially inducted into the mysteries of the ivories by his brother’s wife-to-be, who showed him a simple party piece, out of which emerged an understanding of its basic structure, which in turn led tonan ability to break down the whole and re-chunk it in different ways. Before long,nhe’d realised muchncontemporary pop music was constructed around variations onnsimple themes and four main chordsnand from there grew to a greater grasp of the instrument. Whennpushed on influences, Bill talks freely about the inevitability of absorbing almost everything heard from his earliest days – ‘’Smile’ by Charlie Chaplin is in there, ‘Moonlight Sonata’…nand then of course the first two nDylan LPs, but I was wide open to listening to anything”– and yet also keenly stresses that the piano itself was always his biggest teacher and influence. Through finding the feelings that spoke out through the keys, he edged his way towards a highly personal and idiosyncratic direct and expressive style.

At the age of 18, Bill headed off to Bangor in North Wales to do a degree in Electronics, a subject he’d been drawn to chiefly as a result of the influence of his uncle Ron, who was a radio enthusiast and owner of assorted old pieces of equipment. It was this passion that spurred Bill on to pay attention in school and get the qualifications needed to move on to higher education: “I stopped mucking about in school because in Chemistry they’d mention batteries and I’d think ‘Oh, hang on! That’s to do with radios’ – and the same in Physics. They’d mentioned magnets and I’d be like ‘Hang on!’ and from there, I just got really into the atmosphere of old radios. I’d buy cheap old radios at jumble sales and take them to bits and that led to being interested in it all.”

However, once there, he found himself increasingly drawn back to music and actively sought out pianos. There were two on campus – an upright and a grand – which he frequently found free and on which he continued his explorations and experiments. However, it was actually a cheap harmonium that proved to be the door into the music business. By 1964, Bill was sharing a cottage up near the mountains, with only infrequent buses into town, and was starting to piece songs together, though with neither words nor vocals just yet. Despite devouring books – a trait that would lead to and nourish the deep sense of seeking Bill later came to feel – by Orwell and Beckett and the like, he’d yet to voice himself. Nevertheless, this germinal work somehow came to the attention of a local beat ngroup, who started playing it at gigs and eventually cut a demo version onto an acetate. Though the names of both the song and the group in question have been lost in the mists of time, this recording proved crucial in what happened next.

On returning to North London in mid-65, Bill slipped a copy of the acetate to a local bass player, whose own group then started playing the song at gigs. Before too long, Bill had been tracked down by a guy called John Boden, an amateur music and recording enthusiast with his own mobile four-track recording studio, which he offered free use of. For the next 12 months or so, John recorded several of Fay’s early offerings (including ‘Sometime Never Day’, ‘Camille’ andn‘Lily Brown’, all later rescued on the Tenth Planet demos set, From The Bottom Of An Old Grandfather Clock), along with work by his older brother John. It just so happened that Boden was related by marriage to another John, John Barker, who managed Unit 4+2, who’d had a #1 hit with ‘Concrete And Clay’ and, through this connection, a recording of another Bill Fay track was arranged in a local hall, with backing provided by half of Unit 4+2, some of Adam Faith’s old band The Roulettes (possibly Russ Ballard and Bob Henrit, who both went on to join Unit 4+2 anyway) and Bill himself.

By some strange and fortuitous chain of events, all this activity resulted seven months later in Terry Noon finding Fay and offering him a deal with Decca. A drummer who had played with Gene Vincent and Them, only to find himself left out of the picture when Van Morrison decided to relocate to the States, Noon had decided to move more into the music industry itself and had contacts at Decca, his old label. By the time he approached Bill, he was already managing Honeybus, who would play a key role in a later stage of his career. Decca had only recently set up their new subsidiary Deram as an outlet for spacious stereo “Deramic Sound” recordings of contemporary rock and pop groups. Putting out startling new releases by Barry Mason, The Truth, The Move, The Pyramid and many more in its early months, the label was clearly a hip place to be.

A session was booked and two Fay originals were slated for his first release: ‘Some Good Advice’ – a strangely flat litany of offbeat nagging truisms set against a moody piano and mellotron – backed with ‘Screams In The Ears’, an intensely claustrophobic tale of social disconnect at some kind of swinging party related over a dark, driving, hypnotic jazz waltz that fades out, as Bill himself notes, perhaps a little too early, just as he’s starting to cut loose and improvise. Not often noted for his humour, the song also contains some grimly funny couplets, such as “Well, they told me the budgerigar committed suicide / but it was you, I saw you put that gin in its water / I was standing by your side”. Backing for the 45 was provided by The Fingers (of ‘Circus With A Female Clown’ acclaim), who’d been roped in as a result of their links with producer Peter Eden, whose biggest claim to fame thus far was having co-managed Donovan early on.

Despite its release date of August ’67, the height of The Summer Of Love, the 45 is clearly coming from a very singular space. Bill has little truck with the notion of the record being psychedelic and saw the single as little or nothing to do with the prevailing mores. “It just happened to come out the way it did. It’s just what I happened to find musically at the time and those words then just sort of came as well. It was just the stage I would’ve been at with the piano,” he notes today. The 45 attracted some positive press reaction and even saw a US release, but was regarded as “lyrically unsuitable” for influential TV show Jukebox Jury and did little in terms of sales.

Throughout this whole time, Bill was having to make sporadic forays into the world of work, notching up an impressive array of temporary jobs in the process: traffic surveyor, fish porter, gardener, cleaner, factory worker, potato picker and so on. Work was, as he notes, easier to come by in those days, and “many people are in work situations where their heart and soul isn’t”. In between jobs, Bill continued to work on songs and cut demos. By ’68, he was aided and abetted in this pursuit by the mighty Honeybus, who were also managed by Terry Noon. Together they cut ‘Just Another Song’ (its music hall roots to the fore, coupled with a peculiarly warped Goons world view), the achingly lovely ‘Maxine’s Parlour’, ‘Doris Comes Today’ (a beautiful baroque song about a music teacher that comes soaked in classical music and has a droll last verse that is, as David Wells puts it, so Carry On-esque that Kenneth Williams should have recorded it!) and the bleakly beautiful folk ballad ‘Warwick Town’. Honeybus themselves recorded both ‘Warwick Town’ and ‘Maxine’s Parlour’ on BBC Radio One sessions and both were considered as follow-ups to their smash, ‘I Can’t Let Maggie Go’, but it was not to be. No original version survives of another wonderful track cut with Honeybus – ‘Yesterday Was Such A Lovely Day (Elsie)’ – though Sadie’s Expression did record a gorgeous dreamy, hazy take that sat unreleased until it finally saw the light of day on Nice, Tenth Planet’s Peter Eden anthology.

By early ’69, Bill’s songwriting had started to change in parallel with his own inner changes. As he puts it himself, “I’d always been a reader of all sorts, but there’s a distance in reading. I came to feel that there was something to find out and that you could find out.” This desire to reach a state of awareness, of knowing, of feeling was very much part and parcel of Bill’s everyday practices and habits of mind. “I had a friend I worked with around ’67, and we used to talk about this and that and all kinds of things. We were both kind of like seekers, I suppose. He had absolutely nothing to do with music, but a lot rubbed off on me from this friend of mine, Bob. We reached a place where we realised we were walking around largely asleep to bigger issues, to a greater reality. We felt that we as human beings had named things like a tree or a butterfly and in the act of naming them, had in a way explained them away. Basically we felt that we were living in one sense within the restrictions of our own heads. So I started to pay more attention to nature, I didn’t run to the mountains or something though. I mean, from say the top deck of a double-decker bus, just looking at things, looking at trees. Part of your head is saying, ‘Why are you doing this? It’s only a tree!’ But I kept looking in an attempt to get outside of my own head. That’s why, on the back on the first album I wanted to have that photo of me, with all the leaves on me, like I’d been sitting there for quite a long time, looking.”

Also very influential around this time was a writer recommended by Pete Dello, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin – a French Jesuit whose works caused much controversy within the church, and who believed, among many other things, that the universe was the living host and that “no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else” – or, as Bill Fay’s old dad once put it: life is people! Out of all of this emerged the remarkable debut LP, entitled simply Bill Fay and released on Deram Nova, an offshoot launched in ’69 intended to be solely a vehicle for progressive acts, and also home to such greats as Hunter Muskett, Denny Gerrard, Bulldog Breed and Galliard.

Clocking in at a little over half an hour, and augmented by various members of The Fingers as well as John Surman, John Marshall and Ray Russell, a jazz guitarist who was to become a closenfriend and ally in the coming years, andnwith lush orchestral arrangementsncourtesy of Michael Gibbs, the 13-song set rewards repeated listens. Lyrically abstruse and delivered in language sometimes verging on the archaic or even Biblical, the songs feel like fablesnor myths that one returns to time andn time again, trying to pierce the heart of and yet one is always left with simply anfleeting flash of meaning – and a pervasive mood of mystery. Themes recur – the natural world, gardens, rivers; the horrors of the world, the war – or all wars, pollution, heroin – but throughout a hope and care and love pervades. The songs are delivered in Bill’s flat, intimate, warm, yearning voice and seem deceptively simple. There are echoes of music hall, church music, pub music, pre-war music, but all delicately framed in swooning Scott Walker strings and big bold brass. Simply astounding.

Despite its praises being sung to the rafters by Jeff Cloves in Zigzag, the LP barely dented popular consciousness, selling little over 2,000 copies. Seemingly unfazed by this, Bill continued his pursuit of ways of being and seeing, moving towards a spiritualnacceptance of creation and creator. Yet with this new awareness came a shadow: “If you become more awake to the wonders of the natural world, if you actually feel that life element, you begin to feel the anti-life element too and begin to want answers to the terrible things that happen in the world.”

It was through this frame of mind that the far darker follow-up LP, Time Of The Last Persecution percolated. The Kent State shootings of May ’70, wherein four unarmed students were shot dead by The National Guard, sparked the writing of the title track and much ill in the world around him convinced Bill that Teilhard de Chardin’s prophesised Omega Point was imminent – a supreme point of complexity and consciousness, transcendent and independent of the evolving universe, a point which can also be seen simply as the realisation of Christ.

Yet to tag the record, released in ’71, as “Christian” is as absurd as labelling it “folk” or “singer-songwriter”. A more pared-back, instinctive, live affair, the lyrics are never remotely didactic. Sure, they may emanate a sense of dread and foreboding, yet they also bleed with a concern for the everyman and the little details of our earthly cares. In the same way, the music switches from coruscating Sonny Sharrock-inspired guitar obliteration to intimate, soulful, tender ballads. The record stands as a radical, complete, self-contained whole and for any of you who’ve yet to experience its shock and awe and wonder, I cannot recommend it enough.

Some of his ’71 and ’72 efforts finally saw the light of day in 2010 on the double CD set Still Some Light, while by ’77 Bill was working closely with guitarist Gary Smith, bowed bassist Rauf Galip and drummer Bill Stratton, also known collectively as improv trio The Acme Quartet. Over the next two years, the four worked on what was slated – and recorded – as a third LP proper, Tomorrow, Tomorrow and Tomorrow. Whilst its sonic palette may not appeal to all Shindiggers, a group with perhaps an unusually high aversion to the mere mention of the word synthesisers, there are still gems aplenty here – Bill’s voice is as ever a thing of understatement and humble distress and musically the record is extremely experimental. As a review in Dusted puts it: “There are synthesirers throughout, adding an ominously plastic feeling to the songs. The drums are frothy and soft, textural as opposed to the driving rhythms on Time Of The Last Persecution. Here, Fay’s previous tight two-minute song structures are generally more amorphous, and prone to disintegrations and tangential excursions.”

Turned down by one and all at the time, the recordings were simply filed away, as new material was then worked on, only finally being released by David Tibet’s Durtro label in 2005. By the mid-80s, Bill’s wry observation that “it wasn’t me who left the music, it was the music business that left me” was becoming ever truer. He seemingly vanished from sight, although throughout this time he continued both to work and to write and record and, in his absence, myths started taking root.

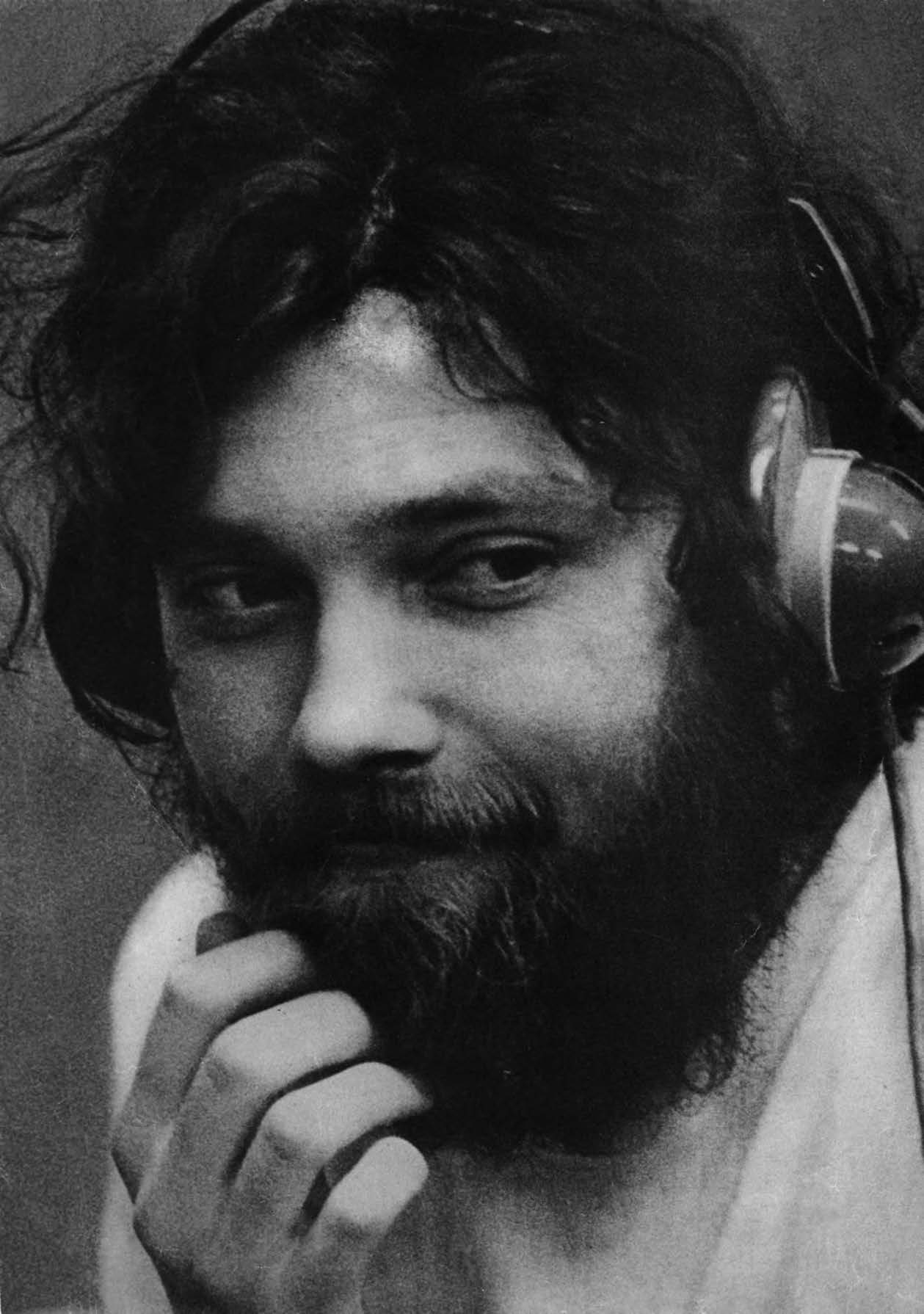

Perhaps as a result of the stark black & white cover of Time Of The Last Persecution depicting as it does a heavily bearded Bill caught in intense concentration mid-song, or maybe due to the lack of officially released follow-up and his apparent disappearance from the scene, or possibly just because of his released output’s dense, confusing, challenging subject matter, the myth of Bill Fay has grown over the years, as of course has interest in the man and his music. The now defunct See For Miles reissued both official LPs on one CD back in 1999, which sparked considerably interest and which also led indirectly to Bill’s slow move back towards his growing public.

Mojo magazine made repeated reference to his work and then in 2004, Wooden Hill released a collection of demos recorded between 1966 and ’70 entitled From The Bottom Of An Old Grandfather Clock, whilst started playing ‘Be Not So Fearful’. English singer-songwriter and pianist also recorded a cover of the song for his EP Songs For The Lost And Found, and Jim O’Rourke ventured forth with a version of ‘Pictures Of Adolf Again’. The internet facilitated increased communication with the man himself and Bill even performed live with Wilco on a couple of memorable occasions, before finally making his all-new and highly acclaimed Life Is People set, out now on Dead Oceans, fully deserving of all your attentions, raved about in more depth in last issue and reviewed in this. While there are no plans for any live shows, the possibility of further releases is very real.

Over the years, Bill has been painted in some corners of the press and indeed the blogosphere as a tragic doomed loner, but mercifully the reality is far more prosaic – and indeed more heartening. Just as a painter lives by painting, working on that which puzzle and bewitches, fulfilling meaningful wishes, discovering, uncovering, so Bill Fay has lived a life immersed in songs and music. He continues to live a normal North London life, and yet also remains keen to stay awake to the world and to the spiritual within. He’s keen to refute any notion of being a recluse or a burnout and is a wise and wonderful man with whom to converse. Indeed, he’s often said that he’d rather his music was lost and forgotten forever than listened to in the hope that it somehow provides windows into the interior world of a broken soul!

To finish right back where we started, Bill recently mentioned to me that an early influence was John Steinbeck and that he was particularly moved by the scene in which an old man and a young boy sit in a tree and chew over the essence of life. Having met Bill and enjoyed his company immensely, I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to share a branch and can only end by thanking him for the many blossoms he has proffered us.

Postscript

Since Hugh’s fantastic article was published in Shindig! issue #129 Bill Fay released another two albums on Dead Oceans, Who Is The Sender? (2015) and Countless Branches (2020), both gaining accolades and further appreciation. He died on 22nd February in his beloved North London.