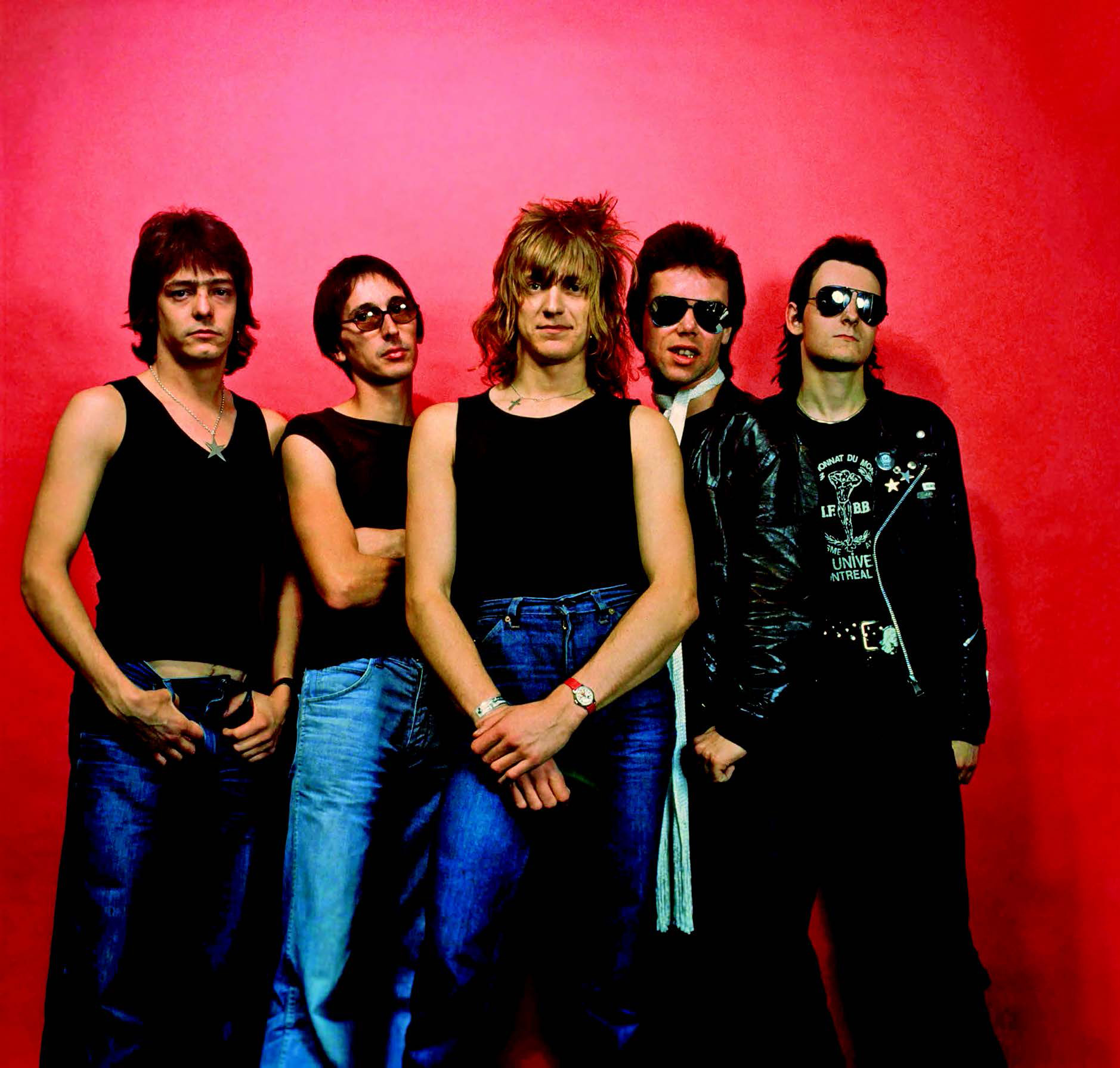

Issue #171 – Eddie & The Hot Rods

Fifty years on from their formation, EDDIE & THE HOT RODS remain a band apart. Fiercely resisting labels, they turbo-charged pub-rock with raw R&B energy and breakneck speed – bridging the gap to punk and proving that attitude, not artifice, could ignite a new era in British music.

CLIVE WEBB buckles up for the ride.

“We were just doing it because we’d got to. No other reason”

After more months of relentless touring, 1977 marked a turning point. Former Kursaal Flyers guitarist Graeme Douglas joined the band, making his debut at Finsbury Park in February. Douglas’s position in the band came with a catch: CBS still held him to his Kursaal Flyers contract, so legally he could not be counted as a full member. Even so, his contribution in shaping their sound was crucial. “He was the right person to come along at the right time,” recalls Gray. “He had a great ear. We’d been gigging incessantly since mid-75 and I think Dave was struggling to come up with the songwriting goods. He and Graeme complemented each other so well – Dave with his extraordinary rhythmic intensity and Graeme with his pop sensibility.”

The first release from the revamped band was the single ‘I Might Be Lying’, which narrowly missed the Top 40. While it confirmed that Higgs still had his creative spark, the B-side, ‘Ignore Them (Still Life)’, with lyrics inspired by the mayhem of a European tour, showcased the melodic touch Douglas brought to the band.

A few months later came the At The Speed Of Sound EP, which featured four tracks including a wired cover of The J Geils Band’s ‘Drivin’ Man’. Although recorded live at The Rainbow, the record required studio overdubs from Douglas because his guitar didn’t make it onto the original multi-track.

The band maintained their hectic touring schedule throughout the year, playing the Reading Festival and a North American tour where they shared bills with The Ramones and Talking Heads. “The New York Times was very disappointed that we weren’t preaching some sort of political revolution,” asserted Douglas, “but after America’s initial surprise that we weren’t coming on in plastic trousers and once they found out that we could play a bit they started treating us like a rock ’n’ roll band, and it went down pretty well.” There were also some internal causes of friction. While the group scraped by in budget digs, manager Ed Hollis splashed out on luxury hotels, a situation that caused some resentment.

By now Higgs had succumbed to writer’s block, so Douglas stepped up as principal songwriter. In rapid order he produced two of the band’s most iconic songs, ‘Quit This Town’, and what would become their defining anthem, ‘Do Anything You Wanna Do’. The first grew out of lyrics Hollis handed over with the instruction “Think MC5 meets Iggy & The Stooges”, while the second took its inspiration from the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley and his dictum, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.”

Released in July ’77 under the abbreviated name The Rods, ‘Do Anything You Wanna Do’ became the band’s biggest hit, climbing to #9 and holding its place in the Top 75 for 10 weeks. The song signalled the shift from the band’s raw pub-rock roots towards a sleeker, powerpop edge. Opening with chiming guitars and a driving rhythm, its lyric (“Gonna break out of the city/Leave the people here behind”) was a defiant call to personal freedom that made the song a rallying cry for restless youth. Critics showered it with praise, naming it “Single Of The Week” across the music press.

The band took their anthem to the nation via Top Of The Pops and Marc Bolan’s television show, sealing its place as one of the year’s defining singles. Not that their small screen appearances lived up to expectations. “Tiny studio, shit stage and sound, and you had to hang around all day,” sighs Gray. “We spent most of the time between takes in the license-fee funded bar taking the piss out of ‘celebrities’. I remember being so excited at sneaking in to watch Legs & Co, then watching them flop down after, fire up the fags and moan about their aching tibias. Welcome to reality!”

‘Quit This Town’ appeared five months later, steeped in the same spirit of escape as its predecessor. Urgent guitar lines drive the track, with Douglas layering melodic flourishes over Higgs’s raw, hard-edged rhythm to create a tense, propulsive energy. The single did not match the success of ‘Do Anything You Wanna Do’ but still broke into the Top 40, peaking at #36 and holding its ground for four weeks.

Coinciding with the single came the band’s second album Life On The Line. Produced by Hollis and engineered by a young Steve Lillywhite, it showed how far they come from their pub-rock beginnings. Douglas now dominated the songwriting, his melodic sensibility shaping much of the record, while Higgs – once the band’s main writer – contributed only one track, ‘Beginning Of The End’.

The album also marked the emergence of bassist Paul Gray as a writer. “The first thing I had the courage to present to the group was ‘What’s Really Goin’ On’,” he recalls. “It was simply a pretty manic bass riff with some cobbled-together words about not being able to sleep from doing too much speed. My world view was still pretty limited at that stage!” The album brims with energy, from the opening salvo of ‘Do Anything You Wanna Do’ to stand-out cuts like ‘Telephone Girl’. Creem captured critical opinion in seven brisk words: “Life On The Line is a beaut!” Charting at #27, the album remains their most enduring artistic statement.

Nineteen seventy-seven was the year during which Eddie & The Hot Rods were at the height of their critical and commercial success. Less celebrated – but no less intriguing – was ‘Till The Night Is Gone (Let’s Rock)’, a single recorded with MC5 frontman Rob Tyner and released a month before Life On The Line. “Lovely fella. Absolute gentleman. The best voice in the history of rock ’n’ roll, for me,” enthuses Gray. Tyner had flown in from Detroit to write about the punk and new-wave scene, and the connection was instant: “I think he loved the HRs as much as we loved the MC5.” Gray still treasures Tyner’s handwritten lyrics and remembers him strumming chords on an autoharp: “I think we all rushed out to buy one after that!” Tyner even joined them onstage at a Colchester festival, his voice cutting through the chaos as the crew stripped away monitors mid-set.

To read the whole story order issue #171 here. Subscribe to the mag here.